Hélio Oiticica, P15 Parangolé Cape 11, I Embody Revolt (P15 Parangolé Capa 11, Eu Incorporo a Revolta) worn by Nildo of Mangueira, 1967. Courtesy of César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro. © César and Claudio Oiticica. Photograph by Claudio Oiticica

One of the most innovative artists and thinkers of the past century, Hélio Oiticica is currently being honored with an in-depth survey that breaks down key moments and artistic endeavors from the artist’s short but impressive career at the Whitney Museum of American Art. From his early days as part of the Neo-Concrete movement in his native Brazil to his time in New York’s East Village during the 1970s’, Oiticica’s inventive practice unfolds in sequences and segments throughout To Organize a Delirium, offering the audience a nuanced and participatory experience that exceeds traditional limits of art viewing experience, a point that strengthens his own conceptual engagement with art itself.

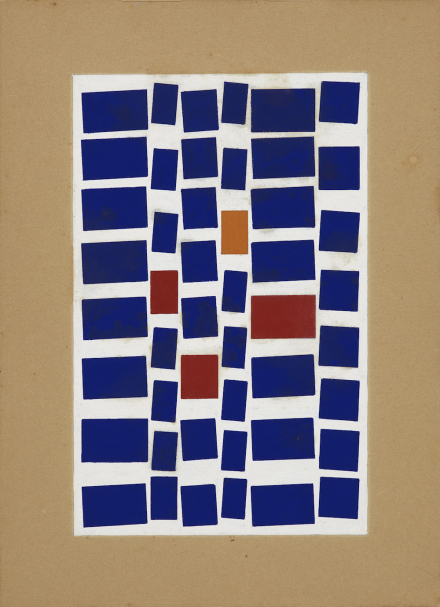

Hélio Oiticica, Metaesquema, Malekledrian (1958). Gouache on cardboard, 9 3:4 x 6 1:4 in. (24.76 x 15.88 cm). The Ortiz Family. Photograph by Joseph Hu

The earliest works in the exhibition introduce Oiticica’s experiments with form and color in minimal abstractions: gouache on cardboard paintings from the ‘50s merging poetic vision with mathematical precision. Composed in mysterious harmonies, geometric forms and bright colors, arranged on mundane and accessible materials like cardboard, signal his ceaseless interest in socio-political dynamics in his native country and around the globe. By the end of this decade, the artist had begun his transition toward three dimensionality, switching his core medium to plywood. With its architectural possibilities and smooth presence, plywood turned into an almost endlessly malleable aesthetic form in the artist’s skillful hands, particularly in works such as P52 Spatial Relief or P41 Bilateral, Teman. By the mid ‘60s, Oiticica had turned his interest for sculpture into immersive installations that even eclipse traditional three-dimensionality. This era is emphasized by the inclusion of his colossal installation NC6 Medium Nucleus 3, for which he employed wood fiberboards painted with oil and resin, questioning the spatial and philosophical extents of the exhibition space. Building an array of surfaces in mysterious order, Oiticica dissects the flatness his material, while immersing the viewer into rhythmic abstraction.

Miguel Rio Branco, Babylonests (1971). Digital projection, dimensions variable. Courtesy of César and Claudio Oiticica, Rio de Janeiro.

Following works such as B11 Box Bólide 9 and B34 Basin Bólide 1, which required activation with audience participation, Oiticica delivered arguably his most recognized work, Tropicália, in 1966-67. Reacting against the commoditized, exoticized profile of Brazil while the country was facing a dictatorial regime, the artist built this subverted version of a paradise island in which the participants encounter various typical (such as sand, plants, and birds) and unexpected (such as pile of books and magazines) objects throughout their sojourn.

Hélio Oiticica, Tropicália (Installation view) (1966-67) Plants, sand, birds, poems by Roberta Camila Salgado on bricks, tiles and vinyl squares. Collection of César and Claudio Oiticica. Photograph by Matt Casarella

With the end of this decade, when Brazil’s political system had already restricted artistic expression, the artist made an exodus to New York, joining a burgeoning hub of artists, writers, and performers, that also served as a refuge for the queer community. Fostering friendships with East Village avant-garde mainstays such as Jack Smith and Mario Montez, the artist built himself a circle for whom he hosted gatherings under the term “creleisure”, a portmanteau expression he made up with the words creative and leisure. The vibrancy of these days, under the influence of rock music and psychedelic drugs, culminated in various slide shows Oiticica created to document his friends or strangers among which were mostly young, beautiful men. His return to Brazil in 1978 was followed by his sudden death in 1980 when Oiticica was forty-two years, full of ideas he had conceptualized into proposals, but not yet realized.

Hélio Oiticica, To Organize Delirium (Installation View, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, July 14–October 1, 2017). From left to right: PN1 Penetrable (PN1 Penetrável), 1960; P34 White Painting (P34 Série branca), 1959; Untitled, ca. 1960; NC1 Small Nucleus 1 (NC1 Núcleo pequeno 1), 1960. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

Tracing the artist’s landmark impacts and boundless creative energy, Hélio Oiticica: To Organize Delirium is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through October 1, 2017.

—O.C. Yerebakan

Related Link:

The Whitney [Exhibition Page]