Danh Vo, Your mother sucks cocks in Hell (2015), all images courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery

Vietnamese-born Danish artist Danh Vo and his family fled Vietnam in a homemade wooden boat a few years after the Communists’ victory, when Vo was just four. In his current exhibition, “Homosapiens,” at Marian Goodman London, as in much of his body of work, the intersection of the historical and the personal is explored through artifacts, documents, and photographs—fragments, begging for the viewer to find their context, that bring into question the nature of identity and belonging.

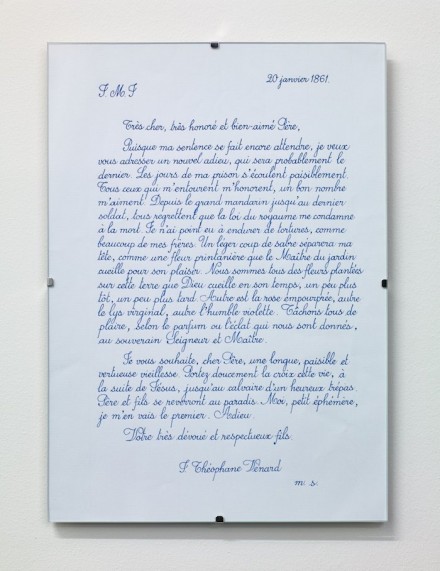

Danh Vo, 2.2.1861 (2009–)

Vo’s family has a presence in the exhibition in 2.2.1861 (2009–). The date in the title of the piece is the date French Catholic Saint Théophane Vénard was beheaded for illegally proselytizing in Vietnam. The letter is the last correspondence Vénard had with his father, written from the cage where Vénard spent his final two months. In it, he writes in French, “A light cut of the sabre will separate my head, like the spring flower that the Master of the garden picks for his pleasure. We are all flowers planted on this earth that God gathers in his own time, some a little sooner, some a little later.” Vo’s own father, Phung Vo, has meticulously transcribed the in blue ink and beautiful script numerous times despite not knowing French. Each transcription is completed at a buyer’s request and personally mailed by Phung Vo. The total number of transcriptions of this letter will remain unknown until after Vo’s father’s death.

Danh Vo, Dimmy, why you do this to me? (2015)

The beheading is reflected in the dismembered statues composing multiple pieces in the exhibit. In Your mother sucks cocks in Hell (2015), the head of a wooden Madonna and child statue rests upon a marble fragment of a child’s legs, the two pieces separated by a flimsy piece of plywood. The Madonna stares forlornly down out the window in front of her. Dimmy, why you do this to me? (2015) has the torso of the same Madonna, disintegrating and with bits of paint clinging to the surface, perched upon the buttocks of a satyr in an unsettling combination. Lick me, lick me (2015) shows a milky white marble torso, sliced neatly down the center and lain in a milk crate. All three take their titles from the 1973 film The Exorcist. The act of breaking apart a statue of the Madonna, an extremely important figure in Christianity and especially Catholicism, and piecing her form together with other body parts seems to fit well with the profane and devilish titles given to these pieces.

Danh Vo, 18.10.1860 (2015)

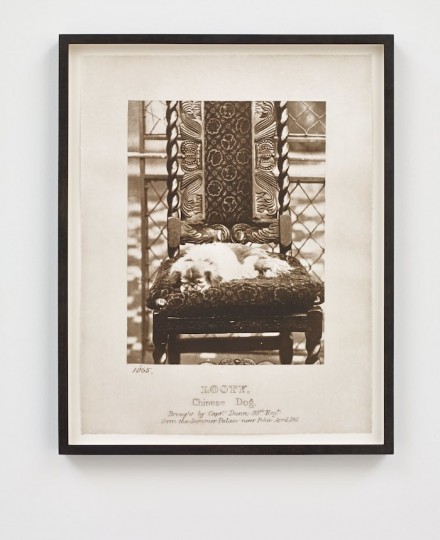

Another brief transcription can be found on the floor in pencil: a line from the song “Afraid” by the German singer Nico. As the audience walks through, the already faint words will continue to fade. “Cease to know or to tell or to be your own / Have somebody else’s will as your own.” The sense of merging identities in these lines reflects the merging of cultures the world has been increasingly experiencing since the spread of colonization. Reflecting that sense of blurring boundaries is 18.10.1860 (2015), a photograph of a Pekingese dog, the first to be brought to the West, seated on a chair. The dog was taken during a looting and burning of the Beijing Summer Palace by British and French soldiers, which started on October 18, 1860, the title of the piece. The emperor’s aunt, caretaker of the palace’s Pekingese, killed herself when the looting started. When given the dog, Queen Victoria appropriately (or perhaps inappropriately) named it Looty. In the photograph, it sits sprawled out on an intricate chair, perhaps sleeping, perhaps looking sadly at the floor.

Danh Vo, Untitled (2015), Nico’s “Afraid” (1970)

—K. Heiney

Related Links:

Exhibition site [Marian Goodman]

Art among the ruins: Danh Vo’s perverse empires [The Guardian]

Danh Vo Revisits The Exorcist at Marian Goodman London [artnet news]