Marcel Duchamp, 3-Mending Standard (1913-1914 / 1964), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

Few artists have left such a mark on the history and direction of 2oth and 21st Century art in the same manner as Marcel Duchamp, the French artist who was at the forefront of revolutions both on and off the canvas in the first half of the century. Taking this impact as a starting point, the Centre Pompidou is currently presenting Marcel Duchamp: La Peinture, Même, an exhibition exploring the artist’s early roots in painting and drawing, and how these stylistic leanings contributed to his later work in the development of the readymade, installation based work, and other conceptual pursuits.

Marcel Duchamp, Anemic Cinema (1925-1926), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

Marcel Duchamp, Paysage (1911), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

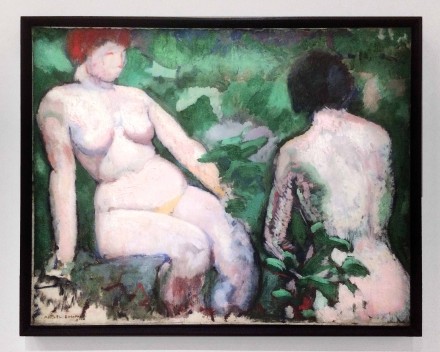

Marcel Duchamp, Deux nus (1910), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

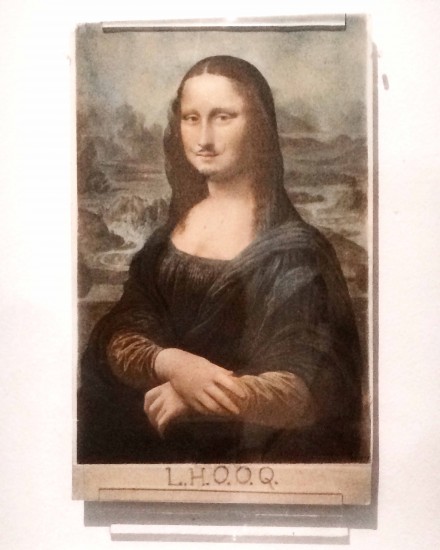

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q. (1925-1926), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

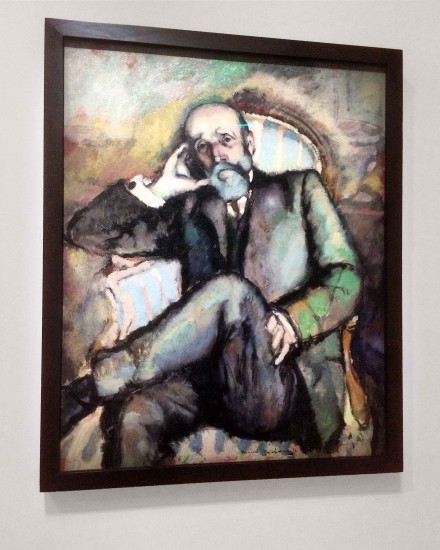

Beginning with Duchamp’s early drawings and paintings as a student, the exhibition explores his roots in loose, nearly Fauvist approaches to figuration, and places these works in the same lineage as his final masterwork, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors. Placing a certain erotic undercurrent throughout his career, the exhibition welcomes Duchamp’s fascination not only with the body, but with its specific dynamisms. His studies of anatomy are placed alongside his interest in the early filmic innovations of the daguerrotype and Marey’s photographic diagrams, as well as works by close friends and family, variations in the modes of looking and seeing that inspired his groundbreaking Nude Descending a Staircase, a painted canvas that signaled his initial break with many of his contemporaries.

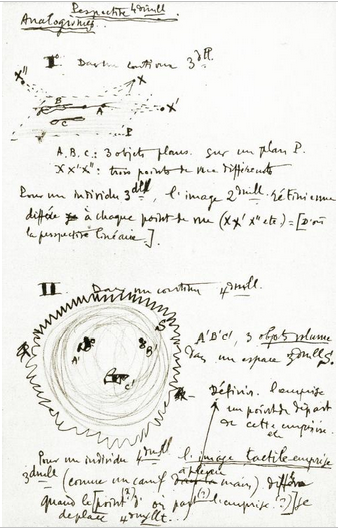

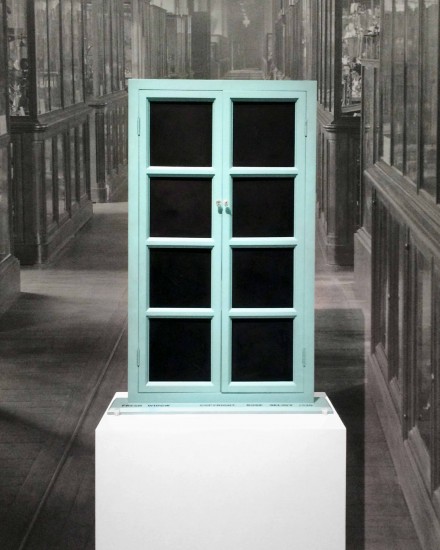

Marcel Duchamp, A infinitive (White Box) (1966), © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI (diffusion NMR) © Succession Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris

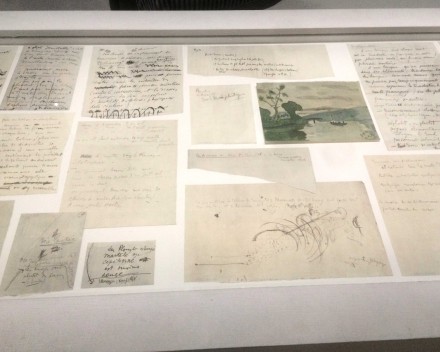

Marcel Duchamp, A l’infinitif (la Boîte blanche) (1966), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

Marcel Duchamp, Nu descendant un escalier n°2 (1912), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

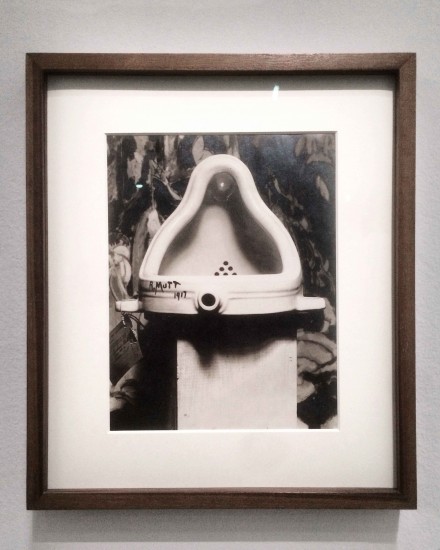

In this context, the mechanical fetishisms of Duchamp’s later compositions, as well as his readymades and other sculptural work takes on a new potency. Observing the object as not merely a static object, but one that may in fact allude to a motion, movement or even circulation as commodity, Duchamp’s work takes on a new emphasis on potentiality, and the dissonance between the lifeless object and the dynamic energies that it references.

Jacques Villon, Untitled (1897), © Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI (diffusion NMR) © ADAGP, Paris

Marcel Duchamp, Portrait du père de l’artiste (1910), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

Marcel Duchamp, Roue de bicyclette (1913/1964), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

The exhibition concludes, quite fittingly, with Duchamp’s Bride, (or rather, a 1/10 scale replica, a point Duchamp would likely find quite entertaining considering his own miniature editions of his work) also referred to as The Large Glass, a quite elusive visual construction that plays liberally not only with its construction as a painted work, but also with the language of his subject matter. Painted on enormous sheets of glass, the work is equal parts a minimal exercise in form, and a strangely compelling visual exercise, contrasting sharp, abstract mechanical formats with the loose cloud of vapor floating above in a separate pane.

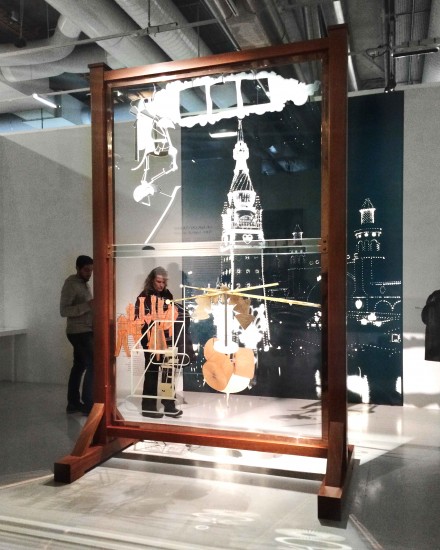

Marcel Duchamp, Painting, Even (Installation View), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

Marcel Duchamp, Etant donnés : 1) La chute d’eau, 2) Le gaz d’éclairage… (1946-1966/1968), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

The Large Glass, complicated by Duchamp’s own mechanical specifications (including his own system of measurement used in its construction), is something of an end game in Duchamp’s techniques and explorations in the painted form, one that addresses both his own fascinations with the erotic and its depiction on canvas, as well as with the mechanical dialogues of the 20th century. His figures, imbued with a certain sexual dynamism by the language used in the description of the work, must constantly contend with the brusque mechanical execution of the painting itself, leaving a certain indeterminacy between the human and the machine.

Marcel Duchamp, Le Grand Verre or La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (1915-1923/1991-1992), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

Marcel Duchamp, Fontaine, photograph by Alfred Stieglitz (1917), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

This dialogue, one that often escapes curator’s approach towards Duchamp, makes the exhibition an engrossing exercise in historical re-examination, taking the painter’s fascination with raw, physical energy, both sexual and mechanical, as a starting point for a new approach to the painted canvas, somewhere between man and machine.

Marcel Duchamp, Etude pour la Broyeuse de chocolat, n°2 (1914), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

Marcel Duchamp, Fresh Widow (1920-1964), via Sophie Kitching for Art Observed

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Marcel Duchamp: Painting, Even [Centre Pompidou]

Marcel Duchamp at the Centre Pompidou, Paris [FT]