Joseph Cornell, Palace (1943), Courtesy Royal Academy

Despite his adventurous stylistic innovations, roving tastes and depth of vision, Joseph Cornell rarely left New York State. The American artist lived much of his life as a textile worker, as well as other odd jobs, while caring for his family in a Flushing, Queens home, while spending his free time creating his massively influential “shadow boxes,” assemblages, films and collaged objects, a body of work that won him praise from Marcel Duchamp, and would go on to influence a range of artists, from the abstract expressionists through to conceptual practices today.

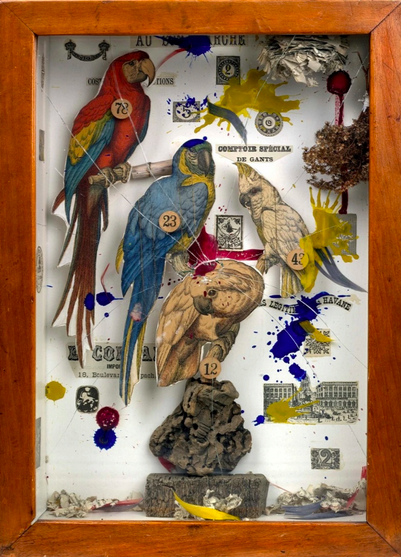

Joseph Cornell, A Parrot for Juan Gris (1953-1954), Courtesy Royal Academy

Working at the forefront of assemblage, collage and Cornell created his own internal universe, compiling cut-outs text and images, objects and other materials that sit at the center of the Royal Academy of Art’s summer exhibition, a retrospective examining the artist’s work that has earned considerable praise. Tying his work to the extended practices both the Dadaists and Surrealists, the show seeks to place Cornell somewhere between reclusive icon and peculiar anomaly, a self-taught artist whose work now sits as a cornerstone of 20th Century art.

Joseph Cornell, Tilly Losch (1935-38) Courtesy Royal Academy

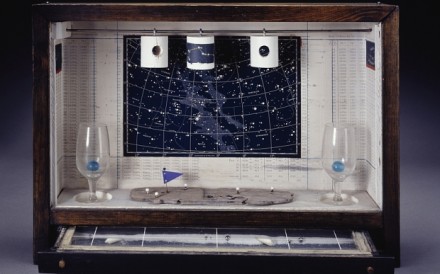

Cornell’s work seems a fitting update on the Surrealist canon, adopting their cut-up sensibilities and imagistic emphasis, and subsequently turning these elements towards some construct of the real. Rather than the still illusory painted canvas surface, depth is a real dimension here, and Cornell’s ability to place real objects into a relation similar to that of the picture plane lends their final presentation a strong, often confounding presence. In Celestial Navigation, for instance, the artist’s glasses, suspended orbs and star charts are not merely metaphorical pieces, but part of an internal, physical logic, and enforce a reading of the work as that of an internally composed structure.

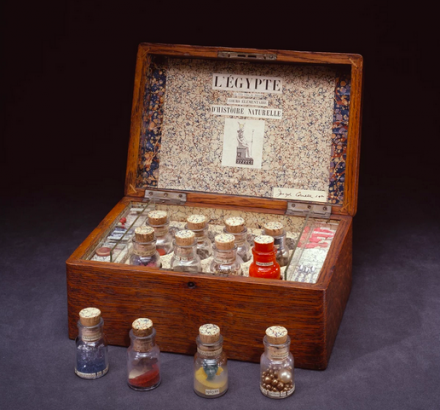

Joseph Cornell, L’Égypte de Mlle Cléo de Mérode cours élémentaire d’histoire naturelle (1940), Courtesy Royal Academy

The artist’s work on view work is dominated by these dualities of presentation: his works look outwards towards a reassembled universe of things, surreal juxtapositions culled from the world at large, while always remaining considered meditations on each individual element, its relation to the work’s narrative, its ties to the other objects presented. Cornell, one could say, was as much a proponent of concrete poetry as the surreal proper. Taking cues from Kurt Schwitters’s assemblages of trash and the banal, Cornell’s work moved towards a sense of treasured, cherished material, using objects salvaged from thrift stores and bookshops around the city. His work feels distinctively of New York as a result, a collection of musty treasures that still seem to populate the antique stores and shops of midtown Manhattan.

Joseph Cornell, Habitat Group for a Shooting Gallery (1943), Courtesy Royal Academy

As the artist’s career progressed, he would move away from his more famed medium, initiating a series of collaborations with filmmakers like Stan Brakhage, the product of which is also featured in the exhibition, before passing away of heart failure in 1972. Compiling this dense selection of objects, films and other works, the Royal Academy offers a striking brand of surrealist escapism this summer, one that welcomes a nuanced consideration of the immediate and the exotic in equal measure, or perhaps, in deep conversation.

Wanderlust is on view through September 27th.

Joseph Cornell, Untitled (Celestial Navigation) (1956-1958), Courtesy Royal Academy

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust [Royal Academy]

Joseph Cornell, Wanderlust, Royal Academy of Arts, review: ‘spellbinding’ [Telegraph]

Joseph Cornell: Wanderlust review – exquisite curiosities [The Guardian]