Alberto Burri, Grande sacco (Large Sack) (1952). Photo: Antonio Idini, Soprintendenza alla Galleria nazionale d’arte moderna e Contemporanea, Rome, courtesy Ministero dei Beni e le Attività Culturali e del Turismo

The chasm between experience and representation seeps through the full expanse of The Trauma of Painting, a major Alberto Burri retrospective at the Guggenheim, an ambitious exhibition that’s as much an exploration in process as it is an embodiment of wartime and its brutal demands on humanity. Born in 1915 in the Italian town of Città di Castello, Umbria, a region steeped in the grandeur of Renaissance art, Burri’s early years were overshadowed by both World Wars. While beginning his career as a doctor, his capture by the British and his internment in Texas during WWII propelled him into painting. Without a formal artistic education, Burri developed a practice stemming from his training as a physician, evoking elements of abjection and corporeal tactility.

Alberto Burri, Grande Ferro M 5 (1958), Courtesy Guggenheim

Exhibition Curator Emily Braun conceives of Burri as a neorealist in this show, acknowledging the ways in which he influenced artists including Lucio Fontana, Eva Hesse, Piero Manzoni, Robert Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly, among others. While resistant to belonging to any given movement, Burri certainly inspired the Arte Povera through his assemblages of everyday, impoverished materials. The Sacchi (sacks) series are a case in point, where he stitches together torn burlap bags with discarded domestic cloths and pillowcases, with crisp white fabric contrasted against the stained surfaces and blackened fields of other materials reflexively affirming the materiality of the picture plane. It has been noted by Braun, among others that Burri’s hand stitching in these assemblages preempted feminist art in the sense of countering gender stereotypes, and deconstructing sewing as a labor exclusive to women.

Alberto Burri, Ferro (1954), Courtesy Guggenheim Museum

As you ascend each level of the museum in chronological order, one gathers a tangible sense of Burri’s growing impetus to attack the canvas, coming further into fruition with the masterpiece Lo strappo, (The Rip, 1952). In this instance we see the canvas as a wound that has been sensitively stitched to express a kind of mending or holding together. Fontana’s slashed canvases would appear a decade later. This notion of sealing wounds is continued in the Catrami (tars) series (ranging from 1948-52). These textured, pitch-black tar compositions were inspired by a trip Burri made to Paris where he saw the collages of Joan Miró, and the inky backgrounds of Jean Dubuffet’s figurative paintings. Burri, in essence, mummifies the canvas, in which the figurative has been completely encased by dense layers of tar. During this time, Burri was also experimenting with distortion in the Gobbi (hunchbacks) series, with steel rods snaking behind the picture plane, causing outward protrusions. Globular, grotesque swellings are coated in PVA emulsion used to bind pigments and to solidify the cracking of the Bianco and Cretti works. The withering skin of works such as Bianco (1952) straddle the lines of repulsion and sensuality, with peeling layers that imply unconventional beauty in decay.

Alberto Burri, Muffa T. (Mold T.) (1952), Godwin-Ternbach Museum, Queens College, City University of New York (CUNY), Gift of G. David Thompson, 1958. Photo: Kristopher McKay © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York

The rich colors of the Muffe series, by constrast, are an extension of the Bianco and Sacchi works, with accumulations of pumice and sand that resemble topographical mappings, and conjure textures of the desert terrain Burri would have experienced during his time in Africa and the Texas Panhandle. The earthy tones enhanced by the shellac recall the coffee and cream colored collages of Braque and Picasso.

Alberto Burri, Rosso Gobbo (1953), ©2015 Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, CittaÌ€ Di Castello: Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/siae, Rome/private Collection, Rome

Burri’s practice evolved further during the 1950s as he began repurposing wood, metal and plastics that correspond to the economic boom occurring in Italy. Known as the Combustioni and Legni, (Combustion and Woods) series, Burri uses an oxyacetylene torch to buckle and burn through surfaces, exposing a tension between chaos and control, ruin and reformation. The cracked canvases from the Cretti series such as Grande Nero Cretto (1977) are unified by their shattering surface, each crevice dramatized by their monochromatic sheen.

Alberto Burri, Sacco H 8 (1953) Courtesy Guggenheim Museum

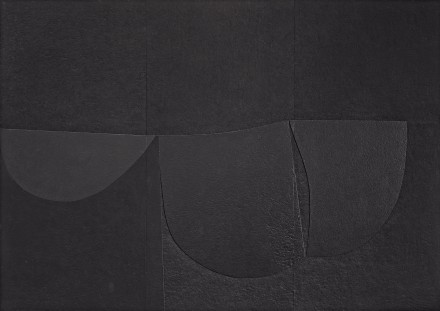

Contrasting the Cretti series, the Cellotex compositions that date from 1975 to 1988 hearken back to the Sacchi series, where Burri comes full circle in his aesthetic trajectory. Works such as Cellotex (1980–89) are coated with black acrylic and Vinavil on Cellotex insulation board, placing layers to form geometric planes in low relief. These works are fully-realized and subtle, intense because they are also understated. Analogous to Burri’s personality and his reluctance to promote himself, his work is regarded for its quietude and meditative qualities. Burri’s oeurve finds its guts in that which is barely there, all the more powerful in its transparency or opacity – and ultimately in its visceral, fluid nature.

The exhibition closes on January 6th.

Alberto Burri, Cellotex, (1980–89), Courtesy Lia Rumma Gallery, Milan and Naples. Photo: Giorgio Benni, courtesy Lia Rumma Gallery, Milan and Naples

— J. Holburn

Read more:

Alberto Burri: The Trauma of Painting [Guggenheim Museum]