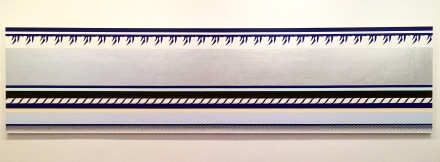

Roy Lichtenstein, Entablature (1975), via Quincy Childs for Art Observed

The Entablatures represent my response to Minimalism and the art of Donald Judd and Kenneth Noland. It’s my way of saying that the Greeks did repeated motifs very early on, and I am showing, in a humorous way, that Minimalism has a long history … It was essentially a way of making a Minimalist painting that has a Classical reference. – Roy Lichtenstein

Sometimes a show strikes a perfect balance between surprise and expectation, even more so when the works selected coincide so effortlessly that the artists seem presented anew. Castelli Gallery’s show, Donald Judd, Roy Lichtenstein, Kenneth Noland: A Dialogue, does exactly that. Taking inspiration from a quote by Roy Lichtenstein on his Entablature paintings, the show examined each artist’s work at the intersections of the architectural and the purely aesthetic, the functional and the pictorial.

Kenneth Noland, Mysteries: Moonlit (2001), via Quincy Childs for Art Observed

An “entablature” is an architectural element, found on classical building facades and frequently utilized in early twentieth-century American Beaux-Arts and Greco-Roman revival styles. During the 1970’s, these designs became a point of fascination for Roy Lichtenstein, the subject of frequent wanderings through New York City to photograph these flourishes of detail on iconic buildings. He was particularly inspired by the rectangular bands of moldings located above columns on urban structures, particularly in their representation of imperial power and, in a humorous way, the establishment entrenched in this minimal nomenclature.

Yet, in his signature practice of absorbing contradictions, Lichtenstein looked beyond the associations of the Neo-Classical ornamentation to create this series. For the artist, these wide horizontal paintings were a direct response to Minimalism, and the work of Judd and Noland. Placing his works alongside Judd’s commanding wall reliefs and Noland’s transcendent color fields, Lichtenstein’s mixture of the two styles offered a clever contextualization, and a sly way to show that Minimalism, with its clean, repeating forms, “has a long history” rooted in Classical architecture.

Roy Lichtenstein, Entablature (1975), via Quincy Childs for Art Observed

Serving as a departure from his signature spotted, comic-inspired pop art from the early 1960s, the Entablatures accentuate Lichtenstein’s conceptual consistency. Like the Ben-Day dots of comic strips, they are reductive images that function in the symbolic realm. Isolated from the associated context of its larger structure, each bas-relief becomes a mechanical reformulation of traditional landscape painting. In a logical progression, the Entablatures develop Lichtenstein’s trademark style towards investigations of postmodernism as a form of repetition, appropriation, and parody. The paintings explore the possibilities of new mediums, blurring the line between fine art and popular culture. Most importantly, though, the Entablatures address the theoretical disparity between abstraction and serial pattern rampant in the twentieth century, with an unexpected allusion to his minimalist peers that this exhibition makes explicit.

The Minimalists’ main premise was that their ideas were a natural progression within the modernist genealogy, from which Lichtenstein regarded his own work. To Judd, the underlying element of his work was its relationship to the viewer and to the space it inhabits – from the confines of a gallery to the stretching deserts of Marfa, TX. To Noland, paintings should transcend the viewer in a purely visual way, with striking compositions of abstract form suspended in pure saturated color and spatial tension.

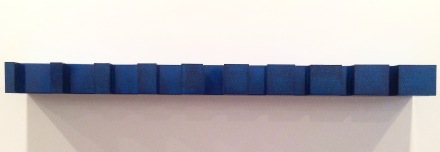

Donald Judd, Untitled (1986), via Quincy Childs for Art Observed

The Entablatures see Lichtenstein taking a stab at both visions through his own brand of anonymous serialism. The horizontal movement of repeated forms suggests an uninterrupted continuation of pattern, an ornamentation that extends to near infinitude beyond the pigment itself. Furthermore, the composition alludes to the conventional divisions of landscape (ground and horizon lines), and lampoons the iconography of the industrial environment through a distinctly anti-human rendering.

Lichtenstein’s reduction of repetitive geometries recalls the additive sense of infinitude that emanates from a Judd relief, or a Noland color field, and similarly, sits stylistically between these washes of color and hard, sculptural lines. A characteristic of Judd’s practice was his serial production of particular forms, with changes made only in materials or colors. He produced a number of horizontal “progressions” in different variations, including Untitled (1987), a tangerine-colored wall relief in the show composed of a series of rounded “bull-nose” fronts. Similarly, Noland’s Half Way (1964) uses four nested chevrons draw the eye to the vertex on its square canvas. This arrangement of lines and muted, warm colors automatically pulls the gaze to the left side of the canvas commanding the viewer to reprioritize their perception, a new, unstable yet unified form. If Judd’s goal is to occupy the physical space it inhabits, then Noland’s is to engage the psychic space that is undeniably present when viewing his works.

Kenneth Noland, Half Way (1964), via Quincy Childs for Art Observed

In his case for minimalism, and the Classical nature of its serialism, Lichtenstein expands the Entablatures outwards from his trademark style of two-dimensional Pop Art. He incorporates new, complex techniques of screen-printed and lithographed areas, variously colored metal foils, each embossed with architectural motifs, resulting in a play on the illusion of real architectural ornamentation, flat abstract pattern, graphic representations, and actual raised reliefs. The viewer is free to play with the vibrancy of the canvases and the resulting imaginations that ensue.

The exhibition implies a theoretical progression between the three artists, wherein the Entablatures serve as a commentary between the two acclaimed minimalists. Lichtenstein underscores serialism in Greco-Roman architecture through Pop Art techniques. The mutual factor of serialism is clearly stressed in Judd’s writings and sculpture, and gives the same sense of additive space, an infinite progression, that Judd’s reliefs deliver. Similarly, Judd’s engagement with serialism places three-dimensional objects in space. When studying them one is sure to experience a visually complex work, in which colors protract, surfaces reflect, and shadows cross upon the wall.

Donald Judd, Untitled (1967), via Quincy Childs for Art Observed

The Entablatures reference Noland in the way they suggest space. Lichtenstein’s new form of a collaged paper relief, with the surface raised and depressed, gives life to graphic abstraction. Ultimately, he toys with the viewer’s perception of space by mixing his signature dot technique with geometric forms, harsh tonalities of dark and light, and burnished metallic structures to disorient the viewer’s sense of psychic space in a similar fashion. Yet Noland anachronistically topples the others’ concern for serial imagery, receding space, and linear horizon lines with a furtive exploration of color. His thin, opaque layers of color assume the role of additive space and form. Mysteries: Moolit (2001), for instance, sees each tone revealed through its own sense of weight, density, and transparency in a radial pattern, negotiating tensions between Noland’s composition and the boundaries of the picture plane.

The show’s ultimate psychological effects formed themselves around this tension of space. Noland rearranges our sense of it, Lichtenstein parodies the eye with it, while Judd activates it with his three-dimensional structures, asking us to reflect on the additive properties it suggests. In this sense, Lichtenstein proposes the context, Noland the question, and Judd, the departing answer, or perhaps an alternative to previous answers. Like all great exhibitions, time itself is curated, the artists enter the room in a dialogue where their respective investigations, and reimagined senses of space and time are explored.

— Quincy Childs

Read more:

Castelli Gallery [Exhibition Page]