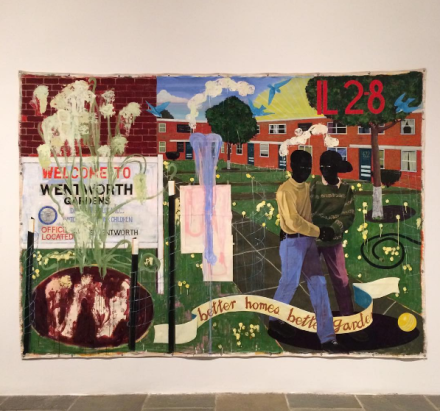

Kerry James Marshall, Better Homes, Better Gardens (1994), all photos via Katerina Paitazoglu for Art Observed

The long-anticipated retrospective of the work of Kerry James Marshall has come to New York, opening its doors this week on an expansive and impressively selected body of works that spans the painter’s wide creative output and varied adventures in the painted form. Ranging from cogently political abstraction and surrealist figuration through to studied depictions of everyday life or quietly executed self-portraits, the exhibition is a fascinating introduction and elaboration on Marshall’s artistic perspective.

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Painter) (2010)

Spread across two floors of the Met Breuer, Mastry runs through a wide range of Marshall’s work, from his early portrait paintings and subtle operations on canvas on through to the massively scaled Garden Project series, each time allowing for varied diversions and tangents through the expanse of art history, always with black subjects and black bodies at the center of his work. Marshall’s ongoing project has sat at the center of much of the language surrounding the show, a relentless insistence on the prominence and presence of the black figure in the images hung on museum walls. “These are things that need to be seen,” Marshall said during the exhibition’s press preview, “and these are things that expand our appreciation of art and our experience of the world when they are seen.”

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Club Couple) (2014)

With this scope in mind, Marshall’s career is something of a masterclass in the exploration of history and visual expression operating in tandem. Utilizing subtle arrangements of visual signifiers, cultural touchstones and a range of varied techniques and approaches to his subject matter, Marshall is able to wind his way through both the annals of art history and his own experiences in tandem. His pieces effortlessly incorporate dense political histories with the techniques of classical icon painting, or operate on the language of post-war abstraction to open space for the articulation and expression of black narratives. Of particular note is his striking Garden Project, on view on the museum’s fourth floor, where the artist twists both traditional painting techniques and a conceptual approach to the frame that allows him to incorporate both the utopian ideals and hopes for the modern housing project, and ominous notes of the often violent landscape these sites existed within during the 1990’s in Los Angeles. Weighing multiple histories and spaces simultaneously, Marshall’s work here is as vital for its modes of historical exploration as they are for his clean, almost effortless sense of gesture and brush movement.

Kerry James Marshall, Portrait of the Artist and Vacuum (1981)

Perhaps most impressive, however, is the range of Marshall’s visual language, perhaps best embodied by the mini-exhibition of curated works that hangs in one corner of the show. Drawing works from the Met’s expansive holdings, including a striking Andrew Wyeth, Renaissance portraiture, and other diverse objects and images from the museum archives, this wing of the show offers an immediate historical parallel for Marshall’s work, and a window into his own aesthetic grounding. Considering the wide range of visual content explored through his selections, one can see the inspiration for the artist’s endless explorations of the painterly form. In a nearby room, his iconic piece SOB, SOB, depicting an emotionally taut domestic scene, is paralleled by an almost effortless seascape recalling the work of Aaron Douglas, with a pair of black figures towering over the work. Dedicating his work to this range of emotional experience, this room is perhaps the best summation of Marshall’s work, a career drawing from his experience of modernity, the full expanse of art history, and a shared cultural imaginary, all on view simultaneously through the artist’s tightly honed sense of the image, and the painting, itself. Considering this ever-shifting fusion of focal points and visual material, Marshall definitively proves why his survey has earned such a commanding title.

Mastry is on view through January 29th.

Kerry James Marshall, The Lost Boys (1993)

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Kerry James Marshall: Mastry [Met Breuer]