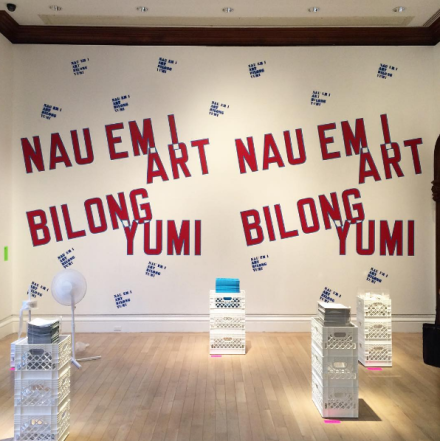

Lawrence Weiner, NAU EM I ART BILONG YUMI (The art of today belongs to us) (1988–2016), via Art Observed

Originally on view at the Monnaie de Paris, Hans Ulrich Obrist and Jens Hoffmann’s curatorial project Take Me I’m Yours has touched down at the Jewish Museum. Bringing together a body of works centered around portability, consumption and distribution, everything on the show can be interacted with or taken by the viewer in some way, allowing the viewer to build up a collection of small-scale works and pieces from a single show.

Yoko Ono, Air Dispenser (1971), via Art Observed

The exhibition is an impressively arranged feat, managing to fill several rooms of the museum’s second floor with a wide variety of work that rarely feels overwhelming in its scale or wieldy in its content. Despite the sheer number of objects available in the show, the logistics for distribution seems to limit the scale of many of the works on view, yet at the same time, also seems to extend the physical space of the viewer out over and into the works on view. Christian Boltanski’s Dispersion, for instance, is a sizable arrangement of clothes in the center of the space, yet the viewer’s ability to reach into the pile, and rearrange its composition while they dig for an object of clothing to take home for themselves, ultimately turns the work into its own self-contained universe. By contrast, Lawrence Weiner’s large-scale installation provides its own perspective on the reshaping of scale and the aura of the work itself, placing a series of tattoos and graffiti stencils in front of the work that allows it to be replicated in various degrees elsewhere, rather than present the work itself as an internalized world of its own. Rather, Weiner presents the work as constantly in transit, spreading its content by repeated installations.

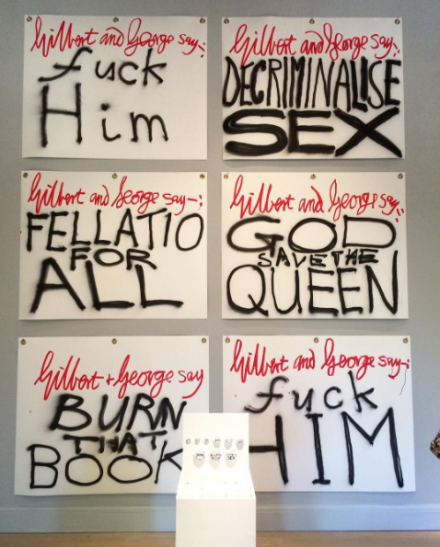

Gilbert and George, THE BANNERS (2015), via Art Observed

Considering these impressively scaled works, other pieces in the show carry a distinctly strong emotional cache from their small size and plays on the concept of the token or memento. Félix González-Torres’s pile of candy is an expected appearance here, meditating on concepts of loss and personal responsibility in terms of the viewer’s participation with the art, but a nearby piece by Claire Fontaine offers a distinctly more dystopian message. In a small dish nearby, viewers can take what appear to be memorabilia coins, marked with the year ‘2016.’ It is only when the coin is flipped over to reveal its other text: “PLEASE GOD MAKE TOMORROW BETTER,” that the consumer is presented with a bleak reminder of the violent political struggles of the modern era. Elsewhere, Gilbert and George’s recent sign-painting practice, with liberal slogans like “decriminalize sex,” offers a playfully militant message fro viewers to subscribe to, and take way pinned to their lapel.

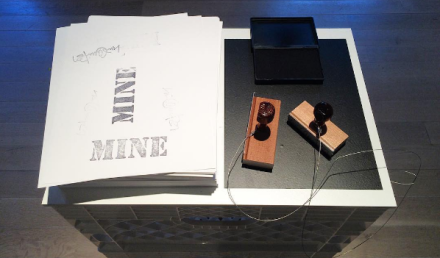

Luis Camnitzer, Mine (2016), via Art Observed

It’s an interesting point to consider the act of affiliation and consumption in relation to a show like this. Aiming to offer something of a counterpoint to easy market politics, the show equally presents the familiar art context of the readymade as an object readymade for immediate consumption. Values, messages and political stances are offered for the viewer to pick and choose, and ultimately to carry far beyond the gallery itself. While the exhibition does little to editorialize in the way of advocacy for a certain politic al or economic vantage point, the mode itself carries intriguing potentials, allowing a consideration of how the mechanisms of the art field can be used to convey messages and transport materials far beyond their original contexts.

The show is on view through February 5th, 2017.

Claire Fontaine, Please God Make Tomorrow Better (2016), via Art Observed

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Take Me I’m Yours [Jewish Museum]