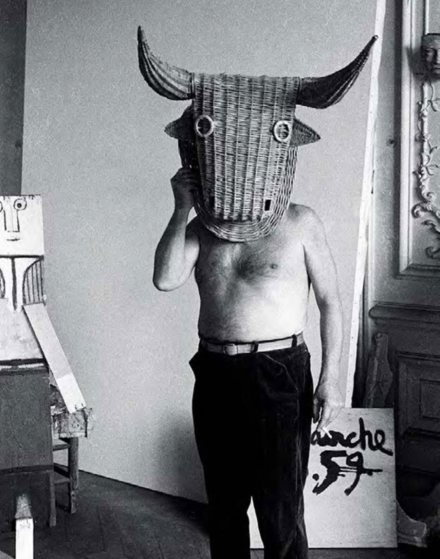

Edward Quinn, Picasso wearing a bull’s head intended for bullfighter’s training, La Californie, Cannes (1959), courtesy of Gagosian

A true Spaniard at heart, Pablo Picasso had a great affinity for bullfighting. With a keen appreciation for the sport, it proved to be a continuous theme throughout his work. Picasso’s oeuvre is riddled with symbolism as well as direct pictorial representations of bulls, matadors and the mythological minotaur— the half-man, half-beast that so piqued Picasso’s interest. Minotaurs and Matadors, on view at Gagosian’s Grosvenor Hill gallery space through August 25th, a show expertly curated by Sir John Patrick Richardson, celebrates Picasso’s passion and link to both his traditional Spanish roots and the mythological landscapes that so inspired him in turn.

A biographer and friend of the late master, Sir John Patrick Richardson was born in London and became close with Picasso and his family during the 1950s while living in Provence, France. During this time Richardson attended many bullfights with Picasso, all the while noting Picasso’s deep level of concentration and appreciation for the matches. A result of their relationship was the three-volume biography, A Life of Picasso, with a fourth book currently underway. It is this nuanced understanding of Picasso, both as a man and artist, showing a level of care and personal connection that is also evident in the exhibition’s curation, and makes Minotaurs and Matadors such a compelling exhibition.

While Picasso’s work surrounding the Minotaur was at its height in the 1930s, the exhibition opens with a simple painting from 1958, entitled Minotaure. A mid-sized canvas, the painting features the face of a Minotaur with the distinctive features of both man and bull. The Minotaur’s direct gaze is both quizzical and commanding, suggestive of the Minotaur’s symbolic nature in Picasso’s visual score, often as a figure in which Picasso can explore his own identity. With a white background the work appears fairly light, particularly as it is set against the lush green fabric that is draped across all of the exhibition walls.

The exhibition features many works that have never been exhibited to the public, as well as drawings, sketches, ceramics and biographical material aided with video projections and image slideshows. There is a range of stylistic explorations, in regard to both color and form, with varying levels of abstraction and tonal shifts. It is arguably through the drawings and sketches that Picasso’s complex relationship with this set of imagery and symbolism is truly exposed. An evolution of identity unfolds, one in which Picasso is manifested through the triumphant bullfighter, the slain bull and the multifaceted Minotaur in turn.

With connections to Mediterranean culture, traced back all the way to ancient Crete, the Minotaur exists as both a hero and a villain— a dynamic mythical creature who wears many faces. Featured in the exhibition are all seven sets of the great ‘Minotaurmachie’ series, where the Minotaur carries a sword, lies with a woman and follows the path of a young girl. In Picasso’s own life the role of sacrificial woman to the Minotaur monster was played by his mistress Marie-Therese Walter. Marie-Therese was merely seventeen when she met the much senior Picasso in 1927. While they never married, they were together until 1940, in which time they had a daughter together and Picasso’s wife Olga left him. Throughout the exhibition are many images of Marie-Therese, including some lovely drawings and other darker renderings, all works that shed light on the multifaceted monstrous figure and the often enigmatic artist.

Pablo Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors is on view at Gagosian, Grosvenor Hill through August 25th, 2017.

— S. Ozer

Read more:

Exhibition Page [Gagosian]

“Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors review— sex and death in the bullring” [The Guardian]