Ibrahim Mahama, (2019-2021), via White Cube

Marking his third show with White Cube, artist Ibrahim Mahama brings together a body of new works addressing the passage of time, the notion of obsolescence and the potential for regeneration. The Ghanian artist, whose work often incorporates materials from the everyday landscape of his home in Tamale, touches down at the gallery’s Bermondsey exhibition space for Lazarus, a show that draws reference from the biblical story of a miracle resurrection and one of Mahama’s works on view, a group of suspended sculptures formed from armatures made of metal rebar and draped with tarpaulin, which together take on the form of cloaked figures or large bats. Haunting and ethereal, the work challenges framings of economic and cultural history in his home country and abroad.

The show draws particular influence from ‘Nkrumah Voli-ni’, an abandoned building located in the northern city of Tamale, and which takes its name Kwame Nkrumah is the name of the first president of Ghana, while Voli-ni, which literally translates as ‘inside the hole’, invokes excavation, teleportation and transformation. Mahama’s work, which often alludes to the early years of Ghana’s independence, here explores the building’s vast interior, which has become a site where the natural environment has once again taken over. The massive Brutalist structure, now home to an ecosystem of fish, reptiles, birds and bats, serves as a fitting metaphor to chart the ebbs and flows of revolution and change.

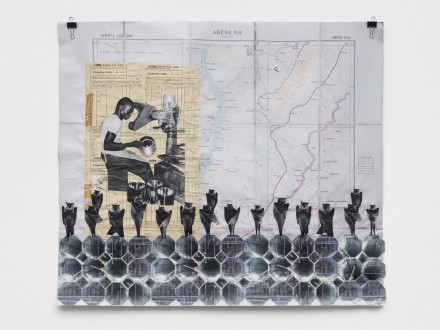

Ibrahim Mahama, Annual Report Series VI (2021), via White Cube

The artist’s new groups of collages, which vary in size from the monumental to the domestic, are mostly named after recent popular music titles, all of which address the climate crisis, reflecting the urgent global paradigm shift. Made up from archival notes, drawings, and photographs, the collages combine repeated images of silos and bats with colonial-era maps, bank notebooks, orders and ledgers from the 1960s and 70s; all now defunct paper residue. Echoing the formations of bats, which hang in rhythmic rows from the ceiling of the silos, the collages are informed by a lyrical, topographical patterning. When considered in relation to historical colonial domination – and its effects of blotting out, spoiling and appropriating – the collage technique embodies the many troubled aspects of Ghana’s multi-layered past.

Ibrahim Mahama, PARAD(W/M)E III (2021), via White Cube

Another work, Capital Corpses (2019−21), erects a series of blackboards, between which one hundred rusted metal sewing machines affixed to colonial-era wooden school desks are sectioned and activated in turn by a timer, creating a syncopated cacophony of noise. A symbol of industrial labor, these machines now emphasize a change in the national economy, and which take on a role as ghosts, remainders of a now past economic hegemony, a record of time and a place where history collides with modernity.

Ibrahim Mahama, All the Good Girls Go to Hell (2021), via White Cube

Mahama’s work often deals with this notion of hauntings, of bodies and times now out of flux with the landscapes around them. Here, in the British capital, which once ruled over the Ghanian landscape during the colonial era, these pieces seem to take on an added emphasis on history and power, leaving reminders of the past floating in face of an unwritten future.

The show closes November 7th.

– J. Shrine

Read more:

Ibrahim Mahama at White Cube [Exhibition Site]