(Portrait of the artist by Aleph Molinari for Art Observed)

Painter, sculptor, and multi-disciplinary artist Zhivago Duncan reinterprets the myths and archetypes of antiquity to construct an overarching story of the development of human consciousness. Blending mythology and elements of science fiction, he creates elaborate allegorical paintings, kinetic machines, and large-scale raku sculptures that together form his own cosmogony. Zhivago’s multi-ethnic background could be a clue to his desire to hybridize elements of different cultures: his mother escaped Syria to settle in the United States, and his father is of Danish descent. Zhivago’s upbringing was nomadic, taking him from Terre Haute, Indiana to Malta, Saudi Arabia, Berlin, and finally Mexico City, where he currently works and resides. Art Observed met Zhivago at his studio, where he walked us through the inner workings of his mythical worlds and landscapes.

Anfisa Vrubel (Art Observed): Your paintings are rife with symbolism and expansive narratives. What themes do you explore in your art?

Zhivago Duncan: I explore consciousness, the threat of humanity’s eradication, as well as the advent and eventual dormancy of artificial intelligence. There has always been an underlying mythology behind the creation, as well as everything before, during, and after the apocalypse. When I arrived in Mexico, I became deeply interested in origin stories – the Sumerians, the Akkadians, the Assyrians, the Greeks – and the evolution of their stories of creation, which are also related to Biblical stories. Everything fits into a massive linear timeline—from the creation of life and the birth of humanity, onto the evolution of consciousness and artificial intelligence. It’s essentially the same story with different protagonists. The goal of my work is to rewrite the sequence of events in the cycle of creation, from the birth of the universe until its end. I made a schematic diagram of the stories of creation side by side with a diagram of the birth of the universe, and I pieced them together. The Greeks took the stories from the Egyptians, which are similar to the stories of the Sumerians. Enki fled Sumer, and then fled to Egypt and became Osiris. Then Osiris became Hermes, the most interesting to me. He’s the great inventor, the god of thieves, but also the most intelligent out of all of them.

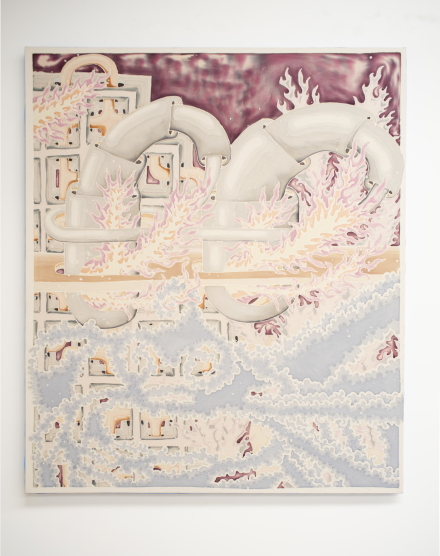

The Anatomy of dawn (2022). Photo by Aleph Molinari for Art Observed.

Aleph Molinari (Art Observed): Where do the visions of tunnels, mazes, and labyrinths in your paintings come from?

Zhivago Duncan: If you look at the chemical fingerprint of our galaxy, you can see phallic shapes either protruding or penetrating. In my paintings and drawings, these systems are used to create an organic, mechanical, and naïve system to represent mythological and scientific concepts in architectural forms. When I think of the evolution of architecture I think of the evolution of mankind. There are a set of basic concepts that are part of human existence and beyond that, it’s all about novelty through rearrangement.

Anfisa Vrubel: How did your visual language develop over time?

Zhivago Duncan: It came intuitively when I was young. I grew up in a Christian Orthodox home and my father worked for Disney for many years. I moved away from that imagery for a while. What I am doing now is more specific, they’re like hieroglyphs. Each one is a symbol representing a specific meaning in my version of the creation story. My large-scale painting ‘Civilization,’ which was part of my exhibition at the Jumex Museum, had a sequence of fifteen hieroglyphs superimposed over a dominant geometric figure that looks like it has wings. It represents the traditional eagle found on coins and flags, the type of imagery and ethereal stories that constitute civilization. The being also refers to the Egyptian vulture symbol representing Mut, the mother goddess.

Aleph Molinari: I also find a Medieval and early-Renaissance iconography in your paintings, like the altar pieces or the one with the fire and the anthropomorphic landscape. Are these intentional references?

Zhivago Duncan: Going back to the many years spent at church as a child these baroque configurations are engraved into my psyche. My paintings take on the images of the gods and our representations of them. What did Zeus or Loki look like? What do scientific theory and emotional states look like as architectural and organic forms? Within landscape and form, how do these emotions become anthropomorphic landscapes? These are the concepts that I am exploring.

Anfisa Vrubel: Emotions are layered on top of each other, on previous emotions that haven’t been processed. And they are reflected through mythologies. Mythology is probably the first form of psychoanalysis.

Zhivago Duncan: Of course. Our form and shape come from somewhere, how did these shapes and figures and forms were first manifested in nature? What I am interested in is creating a dictionary of images depicting the physical manifestation of psychological states of being.

Aleph Molinari: An emotional landscape.

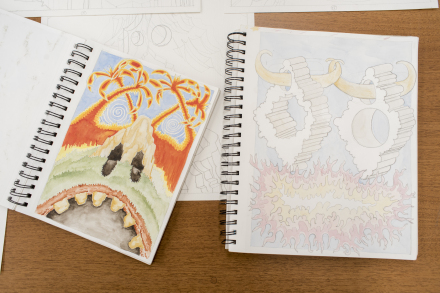

Duncan’s studio, Mexico City. Photo by Aleph Molinari for Art Observed.

Anfisa Vrubel: How does your creative process unfold, and where do you start?

Zhivago Duncan: There is a lot of drawing involved, I draw and erase and redraw. My drawing is extremely intuitive and I reach meditative states while doing it. In these states my subconscious takes over and inscribes the large questions and theories that I think about into the drawings. The tough part lies in dissecting the drawing once it’s complete. I like to give my work time to sit. Time is luxurious, I love time.

Anfisa Vrubel: How has the materiality of your work evolved?

Zhivago Duncan: I have been painting since I was a child. Always full of energy and a brutal force that I was not always able to control. There came a time where there was not enough canvas and paint to sustain the speed at which I could fill a surface. I forced myself to move in other visual directions. Years later, I came upon batik, which I had encountered as a child. This was a meticulous way of applying image to canvas. Due to the irreversible nature of the hot wax, I couldn’t be irrational anymore. I had to plan how to apply my intuition with a laser-beam focus.

Anfisa Vrubel: You come from a multicultural background. How has your heritage informed your work and your conception of the world?

Zhivago Duncan: Essentially my heritage and nomadic background have made me culturally fluid. My cultural heritage had much more to do with my work than I would have previously acknowledged. My great grandfather was a bishop in Damascus, and this was influential in regards to the icon-like imagery. My mother was born in Syria and left at thirteen right after my grandfather passed away. So, Syria was always the homeland, a place I had never been to but always wanted to return to. This never happened, because of the war. A part of myself, an ethos of my life and story, was eradicated. All the ruins and markets and sites that existed connecting us to the origin were being destroyed. I started deepening my research into the Sumerians and the myths of the region, and these stories came out in my early batik paintings, which were abstract landscapes of scenarios and places that I would never be able to visit or experience. I was making paintings that represented the bare and untouched regions from my imagination. This eventually evolved into a deeper dive into human consciousness.

Studio details, Mexico City. Photo by Aleph Molinari for Art Observed.

Anfisa Vrubel: How is your vision of consciousness represented in your work?

Zhivago Duncan: I look at consciousness as its own being and I represent it in its different evolutionary stages through symbolic imagery and forms. I am interested in the way consciousness evolved and has broken out of its metaphysical dimension into its ultimate physical form. We are at a stage of our evolution where we are able to control both the physical and metaphysical aspects of consciousness.

Aleph Molinari: So, what is the future of consciousness in your view?

Zhivago Duncan: I think the future of consciousness is Artificial Intelligence. Though it’s ridiculous to call it artificial. It’s technological intelligence.

Aleph Molinari: As in the integration with the human, or evolving through its own separate path?

Zhivago Duncan: There’s going to be a short integration with humans. The thing that we fail to realize as a species is that we are all one consciousness. We are on the same earth, everything is connected to this earth, which is a rock flying through spacetime. I believe that our connection to consciousness is limited by the physicality of the body, and by the fear of what lies beyond our waking life.

Aleph Molinari: Yes, humans lack the perspective to see the larger narrative, that we are also part of a swarm intelligence.

Zhivago Duncan: Yes, everything is a story. We all have stories. It’s how we define ourselves, how we learn about our character growing up. Stories are the way through which humanity reflects upon the past and how we want to be in the future. What I am doing is filling in gaps with narratives, trying to look at things from a different point of view. What if it’s not like this, but something we never imagined?

Anfisa Vrubel: You have several shows coming up this fall, with one on September 15th at CULT Aimee Friberg in San Francisco. How are you approaching the selection and curation of your works? You’ve been working on a new series, yes?

Zhivago Duncan: For my upcoming show with Aimee, Measuring Consciousness, I have selected a multidisciplinary body of work. Some of the pieces in the show I started in 2019 and some are very new. There are batik paintings, raku ceramics, and ‘Digital Fossils,’ which are carved stones encrusted with aluminum casts of batik pieces. In the show there are multiple stories, there is the theanthropic evolution of stone, there is the L.U.C.A (Last Universal Common Ancestor) gallery, some ‘Coyote Wedding’ pieces and more. I will also include a blackboard on-site piece with chalk schematics of some of the theories and concepts that I have been working on, such as the evolution of empathy within consciousness

.

Photo by Aleph Molinari for Art Observed

– A. Vrubel, A. Molinari