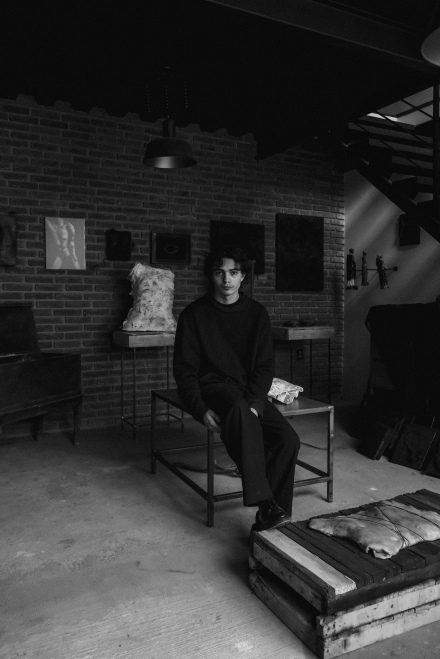

Portrait of the artist in his studio in Metepec, Mexico via Hilario Galguera Gallery

Opening on April 20 at Hilario Galguera Gallery is Mexican artist Gabriel O’Shea’s solo exhibition Preludio. Through his experiments with classical and contemporary mediums, from monochromatic paintings and wax sculptures to AI software, O’Shea explores the complex, and often surreal, relationship between technology and religion in a postmodern digital age.

Art Observed sat down with O’Shea over Zoom to talk about his artistic background, his creative processes, and the major themes surrounding the exhibition.

HANNAH ZHANG (ART OBSERVED) – I wanted to start by talking a bit about your background, how you got started, and how living and working in Mexico has influenced your work. I read in another article how the surrealist backdrop of Mexico deeply inspires your practice.

GABRIEL O’SHEA – When I was twelve years old, my grandfather gave me one of his cameras. He wanted to be a photographer but became a doctor. I come from a family of doctors. I’m the first artist in the family. When I was fifteen or sixteen years old, I was interested in surrealism and how Mexico was the base for many surrealist artists. I think the small details in the streets reflect a lot about the country. Many surrealist things happen in the streets of Mexico. When I was fifteen years old, I started traveling in Mexico on my own with my camera. That’s how it all started.

HANNAH ZHANG – How do you see your early photography in relation to your painting and sculpture, the mediums you primarily work with now?

GABRIEL O’SHEA – In my photography, I was more interested in social themes. When I started painting, I began working from the opposite direction, through a more personal and introspective lens. I felt more connected with the art that I was creating when I started painting. When I was making photographs, I felt that in some sense I was telling other people’s stories.

Gabriel O’Shea, Elegy IV (2023), via Hilario Galguera Gallery

HANNAH ZHANG – A lot of your work incorporates the human body, which inevitably brings up the theme of time – the process of decay, deterioration, and mortality. Can you tell me more about the different ways you’re thinking about the body through your work?

GABRIEL O’SHEA – Yes, I am very connected to explorations of the body because of all the memories from my past listening to the doctors in my family talk about sick patients and disease cases. The sculptural pieces from my series ‘Elegies’ are casts that I used for making wax works. I used plaster casts of my own body and some of my friends’ bodies. I then work on them with all the trash that I have in my studio. So, they are made from remains such as hair, dust, pieces of wood, and bits of animal skin that I found in the streets of Mexico. In a way, they talk about the past and the absence of the body. I’m also addressing the missing people in Mexico. We have hundreds of thousands of missing people. It really inspired me to talk about absence in my work – the absence of the people and absence of the body.

HANNAH ZHANG – When I first encountered your work, I thought immediately of a Yoji Yamamoto interview where he was asked what motivates him to carry on designing, and he said: “Beautiful things are disappearing every day. I want to take it back. I want to say don’t go too much, too far, too easy”. Many elements in your work are expressions of things that are broken, withered, or deteriorated in some way – a haunting confrontation of time and simultaneously, a committed embrace of it. I wonder how you would situate the concept of beauty and presence in your practice.

GABRIEL O’SHEA – I love that question. First of all, I want to thank you for quoting Yamamoto because I’m a big fan of his. The pieces that I made and their material elements, many of them being remains, explore that idea of embracing presence and decay. I like using fragile materials. When the piece is made of things that are considered trash, it’s fragility and passing raises it up to the standard of something that could be innately beautiful and valuable, like a jewel.

Gabriel O’Shea, Symphony of Chaos (2023), via Hilario Galguera Gallery

HANNAH ZHANG – I really appreciate the way you are thinking through material, giving it room to speak and perhaps even grieve for itself. I want to talk more specifically now about this exhibition, Preludio, with Hilario Galguera Gallery in Mexico City. You are focused on exploring the decline of religion in the digital age. How do you view the relationship between technology and religion?

GABRIEL O’SHEA – Growing up, my family was very religious. I started in a religious school and felt very linked with the belief system. When my grandmother died when I was twelve years old, I ended up leaving the school and that’s when all my doubts and questions began. Now, I feel the most “religious” or “spiritual” when I am alone in my studio with my computer. I think a lot of people feel a similar way when they go to a church and have introspective time with themselves. In a normal week, people are just working and not thinking about themselves. I think the internet can be seen as an escape.

HANNAH ZHANG – That’s interesting. I think there is a comparison to be made between the way both spaces can feel transcendent and all-consuming.

GABRIEL O’SHEA – Yes, I feel like this is the first time in history that we can access a kind of second life beyond the physical, the kind of second life that religion alludes to. For the first time we’re able to access a second life that you create online. In the same way religion used to dictate the “appropriate” way people should behave or be dressed, the internet dictates what is censored or what is allowed.

HANNAH ZHANG – Right, parallels between censorship and power. It’s interesting the way you connect the internet to religion because technology is often discussed as a tool of democratization, but you still feel that there is this inherent loss of agency as well.

GABRIEL O’SHEA – I think as time has passed and more people have joined, more rules have been created, and there are now entities that wield most of the power. For example, owners of certain companies act as monopolies deciding what can and cannot be said. Similarly in religion, it would be like a pope or priest who dictated what was allowed or not.

Gabriel O’Shea, The Lament of the Damned (2023), via Hilario Galguera Gallery

HANNAH ZHANG – Looking at your digital prints in this show, can you tell me how your experiments in AI have changed your creative processes?

GABRIEL O’SHEA – I have been working with AI software for about a year now. I started experimenting with AI software, teaching it to recognize my aesthetic. I produced almost 3000 images this year and I selected around twenty images for the show that were connected to the exhibition, Preludio. The more I experimented with AI, the longer and more detailed my instructions would get. I realized that the order I put the words in really mattered. If I put in a sentence with different wording or in a different order, but technically with the same meaning, the outcome would be entirely different.

Gabriel O’ Shea, The Prelude to the End (2023), via Hilario Galguera Gallery

HANNAH ZHANG – The results of your digital productions feel almost inhuman and surreal, and along with the underlying attention to corporality in your works, this exhibition raises many questions around liberation and confinement of identity in our contemporary virtual culture.

GABRIEL O’SHEA – I think it’s important to know that the goal of my art, more than answering questions or making statements, is primarily to cause a feeling of doubt in the viewer. I feel like this exhibition, with two of the major themes being religion and AI, which are very sensitive topics at the moment, will hopefully create many questions and debates. I prefer people leave questioning or having doubts, than for them to leave thinking it was a pretty exhibition.

The show closes July 14.

– H. Zhang

Learn more:

Gabriel O’ Shea: [Works]

Sponsored Post