Madeline Hollander: Hydro Parade at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by Stephanie Berger

On a June evening at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a stream of 15 dancers dressed in sleek costumes consisting of shapes resembling water-bearing vessel handles on their arms and thigh-high rubber waders on their feet, maneuvered through the crowded galleries on the museum’s first floor in a continuous, metronomic fluidity. Audiences staggered closely behind, streaming past grand halls and various antiquity rooms, clusters of tour groups, confused museum attendees, and each other, in an eager, and often entirely coincidental, attempt to keep the dancers in sight. The 90-minute performance titled “Hydro-Parade” was Madeline Hollander’s most recent performance project commissioned by MetLiveArts.

Hollander was initially daunted by the task of choreographing such a highly site-specific performance at one of her favorite arts institutions. With the time restraints, Hollander decided to approach the project as a two-week long research residency; she spent every day at the Met, attending back-to-back tours guided by lighting designers, engineers, maintenance crew, security guards, art handlers, and the museum’s other essential staff members working behind the scenes. “These tours opened the Met, turning it into its own city or planet. I began to learn about the history of the buildings that were sutured together at different times. It’s not just one big building. I began to see how the space was pieced together and the stories behind how that happened” Hollander tells Art Observed.

On one of these tours, Hollander discovered that the Croton Aqueduct, one of the original water distribution systems constructed for New York City, ran diagonally through the basement of the museum. “It almost looked like a subway tunnel,” Hollander describes, “It had these bricks and this beautiful archway. I became extremely excited because it was this incredible feature of the history of New York, running through a massive museum that no one knows is there.” Suddenly, the daunting project began to take form – “Everything became about water. There’s the water running underneath the structure in these specific pathways. The arrangement of the 11 fountains in the museum. All of this was to be expressed through the dancers, made up of 98% water themselves.” Primarily focusing on how water sources flowed through the museum’s infrastructure, its internal system, and its plumbing, Hollander realized how critical the element was to the history of the space and to the history of the city as a whole

“When they were building the Met, they used maps to dig around the wells. Those same maps are still used whenever a construction team is going to break ground. You look at the old maps of all the water streams in Manhattan and you begin to see the city as a luscious island. It serves as a reminder that we’re surrounded by water – that’s not something that you think about every day when you’re just going about your life in this city at the pace that we do.”

Madeline Hollander: Hydro Parade at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by Stephanie Berger

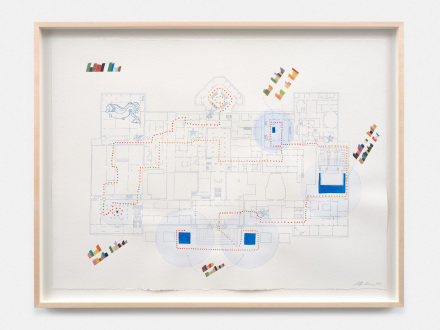

In the process of research and preparation for the “Hydro-Parade” performance, Hollander created 27 watercolor sketches, each with specific color associations through her natural synesthetic processing, that trace the movements and pathways of water sourced from the natural springs beneath the museum.

“Many of the museum’s water features are closed loops and circuits—the water goes out through spout, through the basin, down through pipes, and comes back out through the pump. I started to think about the outline that shape: if you trace the path of one single droplet of water, what is the shape that single water drop would make, moving through space? From there, I began creating these drawings, the sketches of each of the fountains and their location on the map.”

Hollander began conceptualizing the choreography by looking at the patterns that water made through the fountains’ pumping systems, reimagining the outline of the shapes as a sequence of gestures. “We used these pathways as a preliminary score, but the second we performed them in the space and on our bodies, they immediately evolve and morph.” The original trajectory of the parade was to have the dancers pass by and circle all eleven of the fountains in the Met. But given the reality of being surrounded by antiquities and very valuable artwork, Hollander had to present the plan of the project to each of the various departments for approval. In the process, the performance was reiterated and edited. “The shape and pathway of the “Hydro-Parade” loop is actually choreographed in many ways by The Met itself, with all the bureaucratic rules and departmental standards that comes with the institutional space.”

Hydro Parade: Watercolors at Bortolami Gallery

The verbal time-keeping, which became an integral characteristic of the performance, was developed over the course of the daily rehearsals during the Met’s opening hours. While attempting to rehearse in the middle of the museum’s daily crowds and activities, Hollander and her performers soon realized it would be necessary to maintain a vocal counting pattern so the line of dancers could practice various sequences and keep a tempo that they could collectively follow. “It all just became an essential part of the choreography so the dancers could know where to go. All the cues got embedded in that vocalization, which was not intended at the beginning. It’s not something I’ve done before – but it was like survival.”

What resulted from the steady counting was a heightened awareness to interpret the movement patterns as a kind of ritual procession. While the gestures themselves remained soft and continuous, the cadence provided a metronomic form to the performance, a series of prescribed, embodied actions that transcended corporeality as the dancers became representations of the element itself, illuminating the invisible systems in place through the physical body. Performers, costumed as objects and vessels of water, exposed the dynamic contrast between the fluid, malleable nature of water and the strict, exacting rhythm of a parade. “This piece was more abstract in the sense that I was really thinking of the parade as water. I’m not thinking of the dancers as people, but as a stream of water – and we’re going to have the audience transform into water with you,” Hollander says.

Madeline Hollander: Hydro Parade at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo by Stephanie Berger

Carving amusing, fascinating, and at moments, challenging routes, audiences, both intentional and not, became part of the contagious, flowing stream. Forced to decide on how to best maneuver through the crowds and situate their bodies against the current within spatial and temporal restraints, individuals merged into the flow of the performance. “I wanted to design this piece for the random Met visitor, not necessarily an audience member. The goal was to pass through so many rooms and loop around spaces multiple times so the people who are on their way to see the Temple of Denver or grabbing their ticket get a snippet of a performance they had no idea was going on.”

As a choreographer, Hollander’s pieces are always informed and edited by their environments. Looking intently not only the architecture and material construction of a specific space, but also though cultural, historical, and political lenses, her time-based practice interweaves the human body in relation to the existing tangible and conceptual systems at play. “My job is more like that of an archeologist and less like a choreographer. I’m trying to understand what movement systems already exist in these areas and find the people who know them best. These people ultimately become my main source of inspiration for the choreography and aesthetic decisions. So much of the piece is truly a collaboration with the dancers. I want them to really understand the concept and bring their own thoughts, ideas, and movements to it so it can transform into a collective greater than its sum – an altogether new thing. There is no way I could have conceived this without all of them.”

– H. Zhang