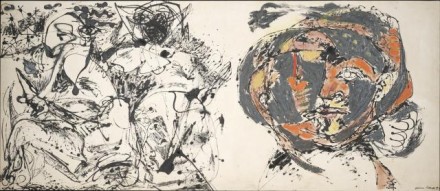

Jackson Pollock, Portrait and a Dream (1953), courtesy Tate Liverpool

Jackson’s Pollock’s early black paint pours return from a 30 year exhibition hiatus this summer at Tate Liverpool, showcasing some of the largest works that were created between 1951 and 1953 in this approach. While often lacking the vibrant color that often defined the artist’s work in the “pour” technique, these works reflect a refinement of much of Pollock’s previous innovation. Many of the artist’s works in this exhibition have never been seen in the United Kingdom, and demonstrate major significance in identifying Pollock’s stylistic shifts during the later years of his career.

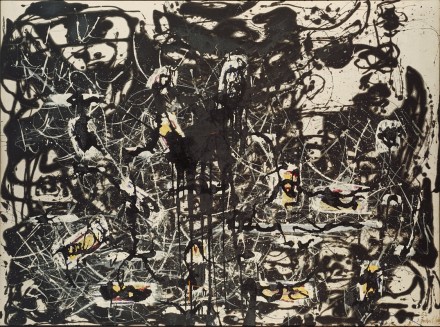

Jackson Pollock, Yellow Islands, (1952), courtesy Dallas Museum of Art

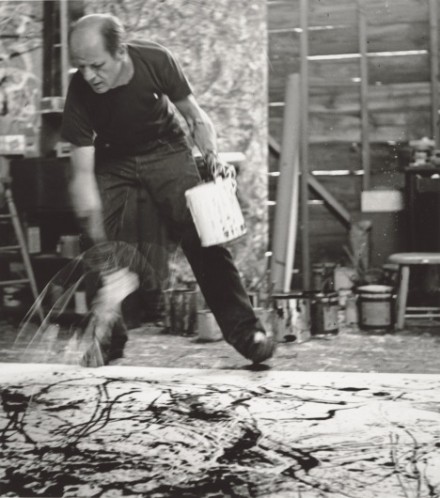

Pollock’s long career of working on the floor had already defined the artist’s approach in 1951, when the artist had felt a need to reinvent his style and refocus his practice around larger, more fluid pours of paint rather than merely dripping onto the canvas. Created during a dark period in the artist’s life, the vivid, black pours shown here exude a dark energy, reflecting the turbulence of the artist’s life, his worsening alcoholism, and the increased pressure from the commercial market after rocketing into the limelight several years earlier. The work here reveals his constant creative vision, tempered and changed by darkened color and grim, emotive impulse.

Jackson Pollock in the studio, courtesy Tate Liverpool

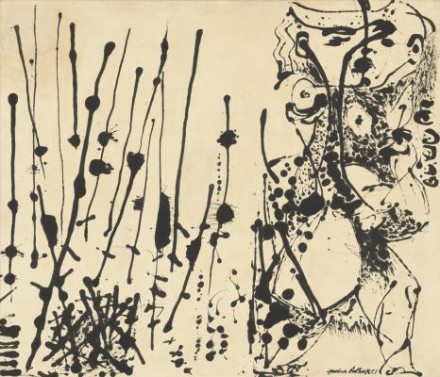

Beginning with his iconic drip paintings between 1947-49 and then moving towards his later black “pourings” in 1951-53, this exhibition provides the opportunity to see Pollock’s breadth of works and practices, while understanding some of the stylistic cues that the artist shied away from in his previous work, or those he moved closer to. Of particular note here is a movement by the artist back towards more recognizable forms and figuration. Alongside the flurry of works like Yellow Islands, faces and bodies often appear in the picture plane, particularly in Number 7, where Pollock uses his own studied hand to pour a cubist sketch of a pair of intertwined bodies. The intertwined bodies are charged with energy, recalling earlier work by the artist while incorporating the full expanse of his creative development.

Jackson Pollock, Number 7 (1951), courtesy Tate Liverpool

Moving away from the core of the iconic aspects of his practice during the late 1940’s and early 1950’s, Blind Spots presents an opportunity to understand both the painter’s engagement with the gestures of the hand and the possibilities for the figure as liberated from mere brush movement. At the same time, the departure from these earlier drip paintings affords one a perspective into Pollock’s own internal politics, and how he worked to structure his compositions.

Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots will be at Tate Liverpool in the UK until October 18th, 2015. The exhibition will then move to the Dallas Museum of Art from November 20, 2015 until March 20, 2015. Special admission prices will be in effect for the duration of the exhibition.

Jackson Pollock, Summertime: Number 9A (1948), courtesy Tate Liverpool

— A. Zlotowitz

Read more:

Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots [Exhibition Site]

“Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots review – revelations in black” [The Guardian]

“Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots, Tate Liverpool, review: ‘a last hurrah'” [Telegraph]

“Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots” [Artforum]