Berlin Metropolis: 1918 – 1933 (Installation View), via Art Observed

Opening its fall exhibition this week, the Neue Galerie looks to Weimar Berlin, with an exhibition that takes an in-depth look at the German capital’s shifting cultural, political and social threads as it recovered from near obliteration into a stable economic power, before descending into the violence and genocide of World War II.

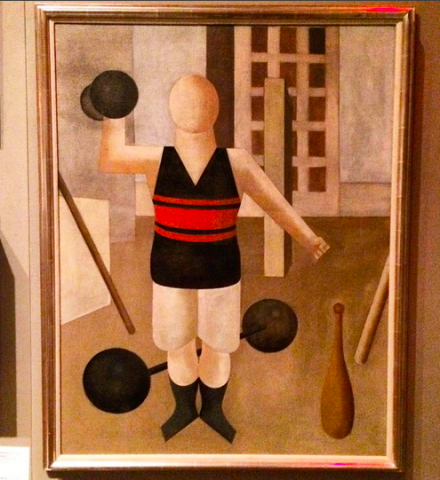

George Grosz, Gymnast (1922), via Art Observed

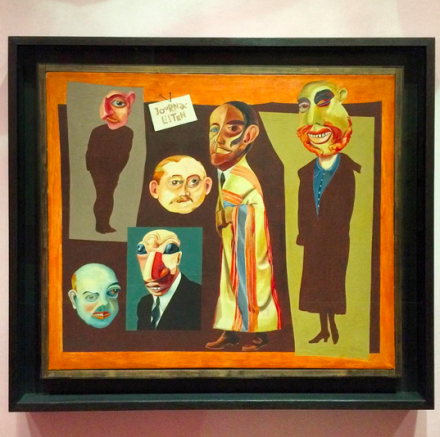

Taking this timeframe in Berlin through a minimal series of frameworks, curator Olaf Peters’s choices all the stronger for the show’s broad strokes, opening the door for connections across disciplines, studies and cultural timelines that offer a maximum of context within the Neue Galerie’s somewhat limited bounds. The exhibition is packed to bursting, spilling over from the third floor down into a single room on the second, where the show begins with a survey of Dadaist and surrealist works from post-WWI Germany. Upstairs, the works are broken into four separate perspectives, exploring architectural innovations like Mies Van Der Rohe’s proposals for a glass-curtained skyscraper in Potsdamer Platz and mass housing projects, before shifting into a study of female liberation and changing identities one room over. It’s this space, with its striking selection of Hannah Höch paintings and collages, that is one of the highlights of the exhibition. Adjacent, a brief study of modern photography segues into the final room, an exploration of the nation’s increased industrial clout and its subsequent slide into Naziism.

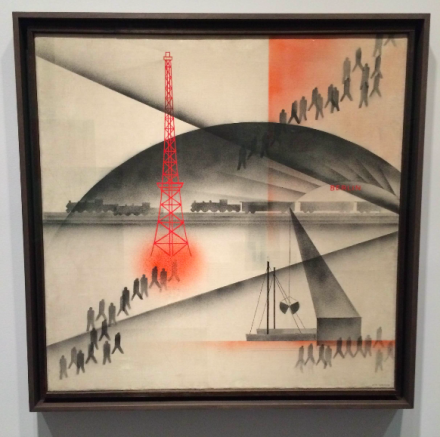

Works by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, via Art Observed

What’s perhaps the exhibition’s strongest point is its dialogue with the exhibitions that came before it. The vivid, often brusque and explosive hand of Egon Schiele, whose exhibition at the gallery late last year was a striking event, can be traced across the interests of the avant-garde that came shortly after him in Berlin. Bookending the show’s focus is the Degenerate Art Exhibitions that came earlier in 2014. Here, one can quite easily trace the line from one to the next, through Germany’s gradual economic stabilization and its sudden turn towards fascism. Yet while the previous shows directed themselves at certain subjects, the broader scope here presents an intuitive look at the era from the perspective of a broader, more general viewpoint of the Berlin avant-garde. Gone are the chilling, aryan statues and faux-heroism of Nazi-era propaganda, replaced instead with John Heartfield’s virulent attacks on the Führer, or the dark surrealism of Rudolf Schlichter’s Blind Power.

Hannah Höch, Journalists (1925), via Art Observed

It’s this last room that carries the show through to its most forceful historical impact, tracing not only the dark rise of the Nazi Party, but a broader atmosphere of Berlin, from the powerful technological revolutions driving the city forward, to the abstract explorations of Moholy-Nagy on the adjacent wall, to George Grosz’s dark, nearly dystopian cityscapes. This new era is perhaps most fittingly summarized by the pair of Fritz Lang films on view (Metropolis downstairs and M upstairs). Moving from the idealistic dreams of revolution that dictate the director’s futurist masterpiece, on through to M’s brooding darkness and challenging empathy for a child murderer, forcing the viewer to confront their own implicit roles in societal violence. Against the background of the changing regimes, Lang’s increasingly despair in human nature seems tangible.

The exhibition offers countless points of inquiry into the German identity during these turbulent yet fertile years for art and design in Berlin, and concludes on January 4th.

Mies Van Der Rohe’s Proposals for Potsdamer Platz, via Art Observed

Herbert Bayer, Lonely Metropolitan (1932), via Art Observed

Oskar Nerlinger, The Early Train (1928), via Art Observed

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Berlin Metropolis [Neue Galerie]