Stan VanDerBeek, Movie Mural (1968), via Art Observed

If there’s one distinct argument coming out of the Whitney’s expansive exhibition Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, it’s a reinforcement of the expression “the story’s in the telling.” Drawing on a wide range of artists and collectives practicing in the late 20th Century and early 21st, the exhibition takes a decidedly narrative bent on increasingly pervasive communication technologies, and the cultural effects that these forms have left both on human interaction at large, and the art world itself.

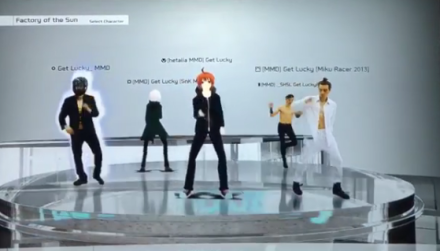

Hito Steyerl, Factory of the Sun (2015), via Art Observed

The exhibition runs through an impressive historical and material span through its course, drawing on classical technologies and their modern, often portable, digital analogues, tracing the variations in function and focus that each era’s investigation of new technologies have wrought. Opening with Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, which places a series of surrealist and cubist signifiers into physical interaction on the film set, one can trace an immediate focus on both the use and critique of the filmic medium. Often dividing the screen into grids, Schlemmer’s images emphasize the illusion of depth, and the screen as a compositional form, a note the show emphasizes with the nearby Hito Steyerl installation Factory of the Sun, which debuted in Venice in 2015. Exploring similar motifs within a space that has in turn been subjected to a glowing blue grid, Steyerl’s work seems to turn Schlemmer’s interests inside out, grafting the viewer into their exchange with the moving image, and the investigations of digital life, violence, and even internet dance subcultures, on-screen.

Philippe Parreno, With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life (2015), via Whitney

Oskar Schlemmer, Triadic Ballet (1922 1970), via Art Observed

These inversions of space and image continue elsewhere to varying focus and effect. Stan VanDerBeek’s Movie Mural for instance, offers an intriguing historical context for the video installation, with a series of projections locking into continued exchange and interaction, allowing implied and interpreted meanings from the vantage point of each viewer as images intersect or collide. By contrast, Jud Yalkut’s Destruct Film presents images in a state of decay, slowly pulling apart and degrading, inside a room filled with destroyed film prints. Implying a movement from a carrier of meaning to a meaningless detritus, Yalkut dives deep for the meaning implied in film itself, and how that meaning persists as its physical bounds are slowly stripped away.

Jud Yalkut, Destruct Film (1967), via Whitney

Elsewhere, artists take a more internalized approach to the construction of both narrative and meaning. Phillipe Parreno’s work on view, With a Rhythmic Instinction to be Able to Travel Beyond Existing Forces of Life. Using hundreds of drawings of fireflies, the video depicts both shifting renderings of a natural form, in conjunction with a computer program designed to algorithmically churn out renderings of cell growth. Turning both analog and digital approaches to the depiction of life into a ever-evolving image of its own, Parreno’s work delves into the generative elements of both, and their shared interest in the idea of life as a generative vector at its more elementary level. Parreno’s work is also part of a more subtle arc running through the show with “Ann Lee,” the female computer animation that he purchased with Pierre Huyghe. Ann Lee appears several times over the course of the exhibition in different works and contexts (including videos by Dominique Foerster-Gonzalez and Rikrit Tiravanija), a fitting allegory for the shifting nature of the filmic character, or the act of personification. Ann Lee is something of an empty signifier, a meaning in herself, that underscores both the constructs of identity and the image in the digital landscape, as her messages and uses shift through the hands of different authors.

Dreamlands (Installation View), via Whitney

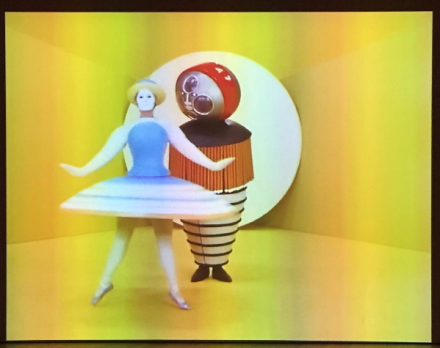

Yet perhaps the most interesting conversation in the show is between artist Oskar Fischinger’s Raumlichtkunst [Space Light Art], an iconic piece of early fine art animation, and a recent work by Mathias Poledna, the animation Imitation of Life. While Fischinger’s work pushes an innovative use of tripartite screens and vivd blocks and color and line to create an otherworldly image, Poledna’s work, shown nearby, revels in an outmoded technology, creating a song-and-dance animation with the help of members of the original Walt Disney Studios animation team. Reveling in a certain sense of both cultural and technological nostalgia, Poledna’s work is a striking inquiry into the act of production in a digital landscape. Now almost non-existent in major film productions, Poledna’s return to hand-drawn animation implies a lost craft and a fetishistic fascination with physical labor in the same breath. Considered against Fischinger’s, which pushes the medium of animation towards a certain clinical distance from mainstream culture, Poledna revels in the labor-intensive forms of the past cultural mainstream, a point that renders the neoliberal economic imperatives of modern computer graphics (and their speed/ease of execution) all the more visible, even as his own power to exploit modes of labor ultimately makes this work possible.

Mathias Poledna, Imitation of Life (2015), via Whitney

This sense of criticality and nuance, spread throughout the works on view, underscore the artist’s range of expression in the modern technological landscape. Dreamlands, by this reading, is as much about possibility as it is about the present, using the tools of modernity to look towards the future, while keeping the concerns of today firmly in view.

The show closes February 5th.

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905–2016 [Exhibition Site]