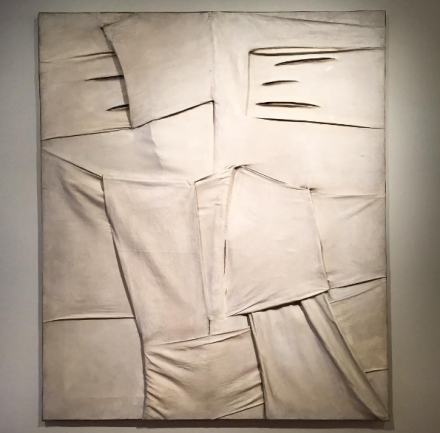

Salvatore Scarpitta, Untitled (1958), via Art Observed

The life and work of Salvatore Scarpitta is defined by the artist’s meandering relationships with his dual homelands. Originally born in the United States, the artist would gain his education in Italy before fleeing the country’s fascist uprising during World War II, later returning after serving in the U.S. Navy’s “monuments men” project, which labored to capture and return looted art and artifacts to their rightful owners. Remaining in Italy for several years after the war, he would pioneer his own brand of abstraction and conceptually-charged minimalism before returning to the States in 1958.

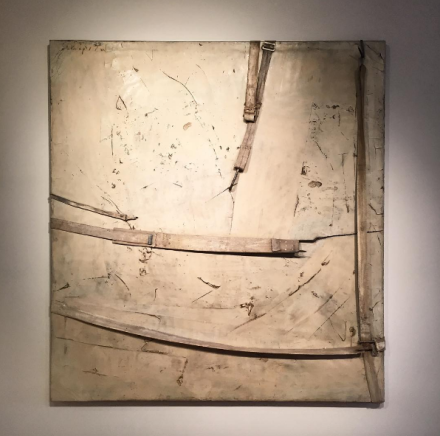

Salvatore Scarpitta, Tishamingo (For Franz Kline) (1964), via Art Observed

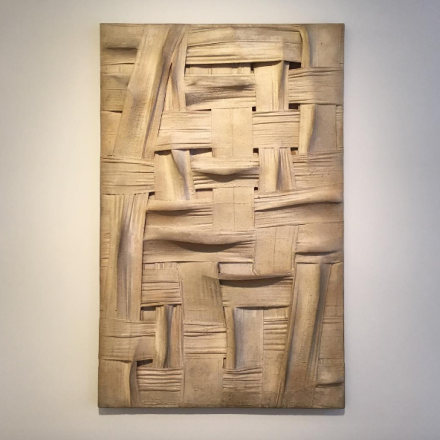

His body of work during these post-War years, currently the subject of a vital exhibition at Luxembourg and Dayan this month, speaks to this negotiation between his place of birth and his cultural motherland; the brusque, energetic charge and essentialist techniques of American abstract expressionism and early minimalism mingles with the pragmatic materialism of Arte Povera. Strips of torn canvas are folded and twisted around the frame’s stretcher bars, often allowed to fold or twist around each other in a way that creates sagging masses of material, or sudden bulges in the surface of the work.

Salvatore Scarpitta, The Corn Queen (1959), via Art Observed

These are works that are highly aware of their position in exchange with history, and make explicit their role in the exchange between the Italian and American avant-garde. There’s no shortage of connections between these two schools of practice, each of which adopt their own interests in the construction of both the canvas and its role in the configuration of space around it, and Scarpitta seems particularly well-qualified to underline these similarities in focus. His works are as much a commentary on the canvas stretcher as an architectural object in its own right, one which defines and shapes the creation of the work on its surface, as they are a meditation on the act of creating itself. This last note sounds with particular resonance in terms of the artist’s own life. Scarpitta was fascinated with concepts of repair and healing, and would compare some of his works to tourniquets or attempts to “staunch a wound.” Like many of the generation in Italy following the war, art was placed in a role as both marker of lost time, and an attempt to heal from the trauma of the violence the country had seen, binding its wounds in an attempt to preserve its larger forms and functions.

Salvatore Scarpitta, Senza Titolo (1959), via Art Observed

Here, mixed with a fascination with pop and the conceptual trends whipping through New York City when he returned to the states, one can trace an application of the artist’s vision and past towards a new framework, one which gradually replaces delicate care with a hardened industrial body, marked no longer by wounds, but the inflection of scars, and bound by new processes and materials. Tishamingo (for Franz Kline) is a particularly notable example: minimal gestural marks on a cleanly executed surface, complemented by bulky straps and buckles, underscores a conversation between the industrial mass production of the post war period, and the historical progression of art that parallels it. Distinctly tied to Scarpitta’s previous pieces, it places a new focus on the object as a skin, a body gradually moving away from its previous injuries, and towards a new, hybridized space, where speed and replication take on new, essential roles. It’s of particular note, then, to consider that Scarpitta would spend much of his later career developing race cars.

Salvatore Scarpitta, Mail Box (1960), via Art Observed

This movement in space and time, symbol and object, makes Scarpitta’s work in the exhibition a fascinating commentary on the history of 20th Century art practice. Offering both historical footnotes and subtle connections in the historical development of the post-War avant-garde, the show traces an artist moving out of War’s chaos, and into a new sense of modernity, one that is still distinctly felt today.

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Salvatore Scapitta: 1956 – 1964 [Luxembourg and Dayan]