Outside the New Whitney Museum, via Art Observed

When the Whitney’s migration downtown was first announced, the anxiety and anticipation over its move away from the Breuer building on 75th and Madison was palpable, to say the least. But as the initial reviews of the space begin to trickle in, the move downtown seems to have made all of the difference for one of the bastions of American fine arts. Sure enough, the museum, which opens its Renzo Piano-designed doors to the public on May 1st, has created the conditions for something truly incredible in the Meatpacking District, an effortless, flowing viewing experience that manages to tie the museum’s impressive holdings together with the skylines and scenic views of its iconic hometown.

Weighing in at over 28,000 tons of steel, glass and concrete, the museum makes impeccable use of its location on the shore of the Hudson, with immense plate windows looking out on both the city to the East and “the rest of the world” as Piano stated during the opening press conference, to the West. Complemented by a number of publicly accessible balconies, a narrative of reflection, on the state of the collection in the context of New York, America, and the globe, flows throughout.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres Installed in the Whitney Stairwell, via Art Observed

America is Hard to See (Installation View), via Art Observed

America is Hard to See (Installation View), via Art Observed

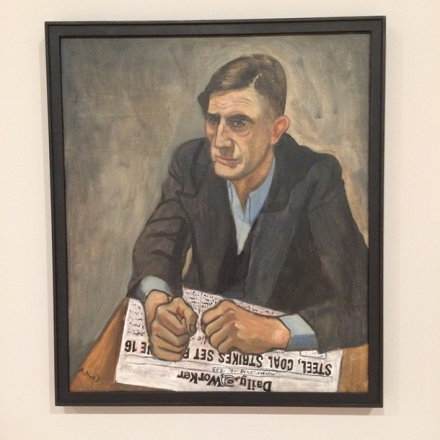

The museum’s debut exhibition then, America is Hard to See, is a fitting statement by the museum, a twisting line that is at turns resonating in its poetry and almost coy in its irony given the space’s soaring windows and remarkable views, juxtaposed with the densely layered challenge of its curatorial mission. Pulling from the museum’s deep holdings, the exhibition traces an intuitive and unbroken line of American art from its earliest origins through to the present day, offering number stops and spots for cross-pollination and examination along the way. Each of the nation’s great moments in classical, modern and contemporary work is writ large across the museum’s long, high-ceilinged spaces, from the Pop Art masterpieces adorning the 6th floor to the early 20th Century abstractions and special holdings on the top floor of the building. In each space, the scenic views around the building are invited in as a backdrop for the museum collection, used to masterful effect on the 8th floor, where a blocky John Storr sculpture plays against the flowing movement of the Hudson below, or two floors down, where a Donald Judd installation of steel frames mirrors the immense window it sits behind, counterpointed against the city’s jagged lines.

But it’s the museum’s 5th floor of recent and contemporary works that perhaps makes the best case for its change of locale. Mixing large-scale sculpture with classic paintings and even installation works, the flexible exhibition spaces and head room underline Piano’s vision. There are few spaces in the city where a towering Nam June Paik TV sculpture could sit comfortably in the same room as a Basquiat, a Keith Haring and a Jeff Koons sculpture, with each work provided enough space for long reflection. Yet this seems to be the norm at the new Whitney. Just one room over, Cory Arcangel’s Super Mario Clouds sits comfortably by itself, as an immense David Hammons and Fred Wilson sculptures are just on the other side of the wall. The rooms flow smoothly together, but the space between them makes for an impressive viewing experience.

Other highlights of the opening exhibition include a massive Mark Rothko from the museum holdings, placed together in a room with a brooding Mark di Suvero and a number of other New York artists, while one floor up, the museum is showing its rarely seen set of Calder Circus pieces, the early works by made by the artist during his time in Paris, that first aided in the creation of his lithe, elegantly curved lines and emphasis on movement. Nearby, a powerful set of staid Jacob Lawrence pieces offer a striking counterpoint, exploring the black experience in the United States during the mid-20th century. But it’s Jay DeFeo’s The Rose that wins out here for sheer impact, a work that long sat in storage due to the logistics of exhibiting its massive bulk, here turned loose in all of its hypnotic, dizzying execution and rippling layers of paint. If there’s one work out of the many masterpieces on view that perhaps best justifies the museum’s new space in and of itself, it may be DeFeo’s, which is finally given the wash of light it demands to truly drive the artist’s mission home.

Matthew Barney, via Art Observed

Richard Serra, via Art Observed

The Whitney could not have picked a more fitting lens for its first exhibition at the new building, and its incorporation of diverse threads of American art and artists from the full depth of its collection underscores the treasures the Whitney is now empowered to offer, while not forgetting the challenges set before it. Even inside the cavernous hallways of its new space, the American ethos remains dauntingly kaleidoscopic, a space where the totality of experience often feels just out of reach. The Whitney would do well to remember this, as it looks out from New York on the rest of the country.

America is Hard to See opens on May 1st, and runs through September 27th.

Edward Hopper, via Art Observed

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Review: New Whitney Museum’s First Show, ‘America Is Hard to See’ [New York Times]

Art Click: The New Whitney [New Yorker]

Whitney museum: America Is Hard to See exhibition tells the stories of a nation [The Guardian]

America is Hard to See [Whitney Museum]

American art gets new home with opening of Whitney Museum in N.Y. [Reuters]

The curators’ guide to the best art at the new Whitney [New York Post]

$422 Million Later, the New Whitney Is Filled With Surprises [Vanity Fair]