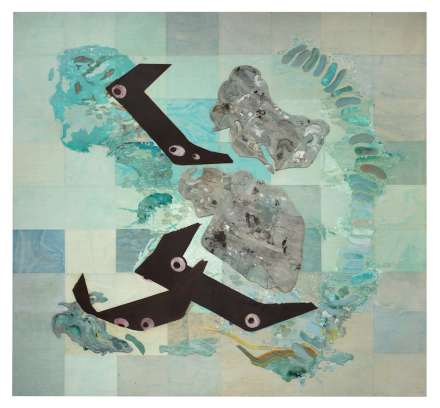

Ellen Gallagher, Whale Falls (2017) © Ellen Gallagher, Courtesy the Artist and Hauser & Wirth

Accidental Records, now showing at Hauser & Wirth LA, is Ellen Gallagher’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles. The collection of paintings, drawings and collage on view includes both new and recent works, which tread familiar conceptual territory while expanding upon themes from her rich and evolving oeuvre. The show’s title reflects the breadth of referential material that substantiates Gallagher’s work—from the literary to the musical, the psycho-theoretical to the culinary. In this erudite exploration of the Middle Passage—the deadly intercontinental journeys of slave ships—Gallagher excavates the depths of black history as well as the oceanic context in which so many slaves died. Known for her minimalist, pop-inflected collages that meditate on the African American body in history and culture, Gallagher focuses her lens upon the Black Atlantic.

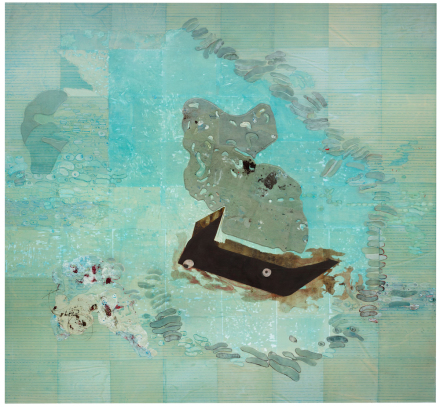

Gallagher, Aquajujidsu (2017) © Ellen Gallagher, Courtesy the Artist and Hauser & Wirth

Fragmented bodies—of ships, creatures, unknown flotsam—scatter across large canvases mottled with inky blues and greens. Built up in thick and varying textures, Gallagher’s paintings envision the tumultuous surface of the ocean littered with splintered shards on dirty foaming waves. Gallagher dives deep into the primordial chaos, its murky currents and treacherous tides, from which both life and death emerge. The abstracted forms that inhabit this watery world consolidate as new and revelatory figures with each viewing, and carry familiar signs of the black body from Gallagher’s work. Wide-open eyes stare out from angular geometries, as though bearing witness to the tragedies and triumphs on this oceanic stage, where haunting faces coalesce in the shards of wreckage, outlined in blood red.

Like Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa (1818-19) or JMW Turner’s The Slave Ship (1840), this nineteenth-century genre of shipwreck presents the brutality of the ocean as well as the slave trade itself. However, the fate of human cargo, thrown overboard in times of storm, sickness or starvation, (even intentionally to be reimbursed by insurance), is not lost to the dark underworld of the sea, but is recorded here in the deathscape of what Gallagher calls “sentient geographies”. One such scene, which presents a vast, churning expanse of water, somehow free of debris (perhaps already sunken), yet agitated nonetheless, derives its title “Hydropoly Spores” (2017) from a song by Detroit techno legends Drexciya. Gallagher is referencing their Afrofuturist mythology, which imagined a utopia wherein the unborn children of these drowned slaves mutated to breathe underwater—creating a life after, or rather, derived directly from death.

Gallagher, Whale Fall (2017) © Ellen Gallagher, Courtesy the Artist and Hauser & Wirth

Such themes of death and regeneration characterize another critical character in these aquatic images—the whale. In yet another nineteenth-century reference to the Atlantic, Gallagher’s paintings look to the whaling industry most famously captured by Melville’s Moby Dick (1851). She refers to this iconic text as an Afrofuturist meditation on the black body—prompting one to see Pip in those big black searching eyes, driven mad while lost at sea. Moreover, Gallagher focalizes the whale—a traditionally biblical reference to rebirth—as a character in the ecosystem of the ocean. “Whale Fall” (2017) alludes to the phenomenon of dead whales sinking to the bottom of the ocean, wherein their bodies will feed hundreds of species. Osedax worms, which exist on these drowned mammoth mammals, inscribe their own accidental records on whalebones, etching their lives onto death like biological scrimshaw. The decomposing corpse, itself resembling a sinking ship, embodies the cyclical transformation of life and death in the oceanic order.

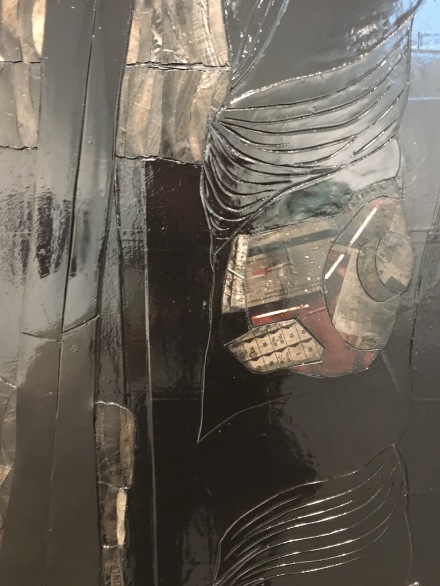

Gallagher, Sea Bed (Sediment) (2017) © Ellen Gallagher, Courtesy the Artist and Hauser & Wirth

Such mythology and meaning are quite literally inscribed upon the pages of a notebook, made from lined writing paper plastered onto the canvas—as the history of the Middle Passage is mapped onto a minimalist grid. This ever-present structure of modernism provides a formal matrix upon which her narratives rest (or perhaps the net in which they are trapped). Like much of Gallagher’s work, they straddle the line between abstraction and narrative figuration, using this paradox to meditate upon the signification of the black body. This same oscillating modality is used in her series of black paintings at the show’s entrance. “Negroes Battling in a Cave” (2016), a suite of four slick black squares, references Kazmir Malevich’s Suprematist black paintings both in form and critique. Their glossy enamel surfaces are interrupted by twisting currents of subjectivity, in patches of newspaper and amoebic forms raised in graphic tactility. The title rehearses the racist joke found inscribed beneath Malevich’s “Black Square” (1915), referring to Alphonse Allais’ humorous painting from 1897 “Combat de nègres dans une cave, pendant la nuit”. This discovery confounds the art historical notion of the absence of meaning in abstraction, illuminating instead the racist narrative that underwrites such blackness. Gallagher discusses “the erasure of black-being and the potential of black paintings” to interrogate blackness as both color and subjectivity, and, as in two early collages included in the show, expose its exploitation in the history of art. (See, for example, her critical assemblage Odalisque (2013)).

Gallagher, Odalisque (2013) © Ellen Gallagher, Courtesy the Artist and Hauser & Wirth

“Kapsalon Wonder” (2015), the largest piece in the show, appears similarly as a black field built up with amorphous shapes both raised in relief and carved into rubber. The shiny surface is both wet and opaque, pierced only by incisions and small collages, featuring again familiar elements from Gallagher’s work, including the stereotypical eyes, lips and hair of minstrelsy and black beauty magazines. Mangled letters dot the surface like ransom notes on this glossy palimpsest. This veneer of abstraction is in fact imbued with a cultural narrative history. Kapsalon is the Dutch word for barbershop, however it has come to refer to a typical shawarma dish in Rotterdam—the port city in which Gallagher lives and works. This kebab ‘collage’ (a compilation of shawarma, French fries, Dutch cheese, lettuce, sambal sauce and spices) was invented by a Cape Verdean hairdresser and represents to Gallagher the act of creation that comes from the mixing of cultures and the transformation of tradition.

Gallagher, Kapsalon Wonder (2105), detail, via Art Observed

Gallagher lives and works between Rotterdam and New York, and is represented by Gagosian. She has had solo shows at the Tate Modern, London; Haus der Kunst, Munich; New Museum, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; and MOCA, Miami. She was the recipient of the American Academy Award in Art in 2000, and had work selected for the Venice Biennale in 2003 and 2015.

The exhibition is on view through January 28, 2018.

— T. Gensler

Read more:

Ellen Gallagher at Hauser & Wirth [Exhibition Site]