Elizabeth Orr, House (2017), via Bodega

In the back room of Bodega, a new video by Elizabeth Orr began with one word: “HERE,” a coy move to set the location before her projected video lit up with a full sentence that manages to double back on the grandiosity of its previous line: “There is no spectacle to be revealed.” This statement, taken in conjunction with the artist’s minimalist sculptures arranged around the front room, sets a terse, self-critical tone for Orr’s new exhibition, Our Hallway is Surrounded, a show that makes much of the act of both creating space, and dispensing with that same space’s contextual aura.

Elizabeth Orr, Our Hallway is Surrounded (Installation View), via Bodega

Orr’s sculptural works seem to be in clear dialogue with art history. They are not merely “influenced” by minimalism, but present themselves as meticulous facsimiles of the cutting-edge work of the mid-1960’s. Even the declaration, “There is no spectacle to be revealed,” presents itself in the same deconstructive tone as that of Frank Stella’s famous line “what you see is what you see.” Or, to take the press release at its most literal, “through a resolutely obscure layering of imagery and tinted glass, Orr’s work reveals nothing but the mechanism of revelation itself.”

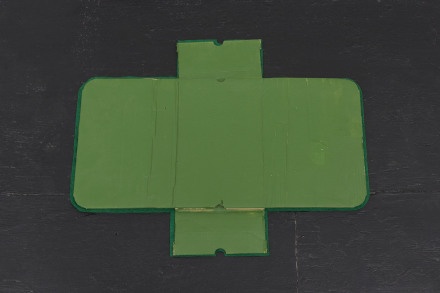

Elizabeth Orr, A Free Economy Farmed and Hunted (2017), via Bodega

That being said, Orr’s video also moves beyond Stella’s tautology. Moments before a green chessboard floats across the screen, a block of text appears, ending with the line, “Morality to the strategy is inconsequential.” While immediately referencing how to play Chess “FOR THE WIN” (another line from the video), her text takes a more interesting tone when applied to the subject of historical minimalism. In excising the pseudo-spiritualism that Ab-Ex painters, like Barnett Newman for instance, lumped onto their work, Orr makes the case that minimalists also threw out the moral imperatives that is often part of any spiritual or religious hierarchies. Or perhaps more notably, they did away with that end of their thinking entirely.

Elizabeth Orr, Hunter (2017), via Bodega

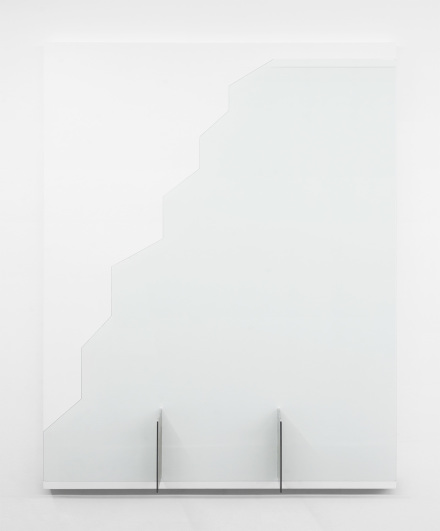

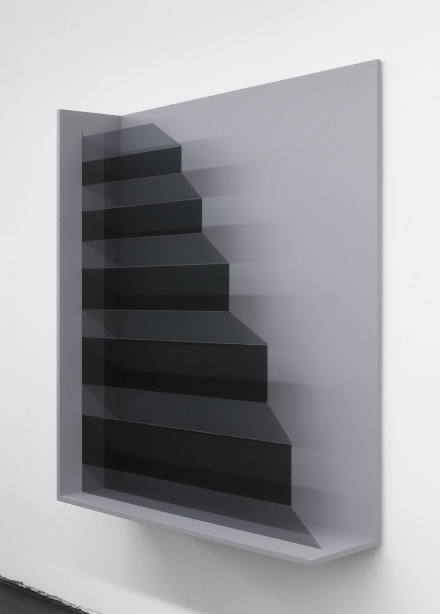

The titles of the five sculptural works also set up a dichotomy between the moral roots of domesticity, or “old country” life and the muddled moralities of technology and academia. Farmer, House, and Hunter refer to a bygone era when a day off from the fields meant a day in church, while Central Server brings to mind the facelessness of the inner-workings of the Internet. Another work, A Free Economy Farmed and Hunted underlines the personal disconnect of highbrow political movements meant to save the proletariat.

Elizabeth Orr, Farmer (2017), via Bodega

Considering the artist’s aesthetics alone, Orr’s sculptures are quiet and beautiful. Each piece straddles the line between sculpture and wall work, with only A Free Economy Farmed and Hunted, a deconstructed cardboard box painted green and backed with felt, standing free from any wall supports. The other four sculptural works, each containing a variety of shaped and tinted pieces of glass, are mounted directly to the walls. The face of Central Server is made up of two pieces of salt stained aluminum, recalling the surface of Carl Andre’s 1969 work, 64 Square Aluminum. Just behind aluminum is a small set of tinted glass rectangles that butt up to the wall. These small glass pieces are revealed only when viewing the sculpture’s profile.

Elizabeth Orr, Our Hallway is Surrounded (Installation View), via Bodega

As visually appealing as these works may be, the more powerful statement is made through Elizabeth Orr’s nuanced rereading of the minimalism movement. Orr does not merely pay homage to a style; she instead reopens the casket to cast light on a complicit body. As the physical signifiers of minimalism spread throughout the gallery, Orr examines how their function and meaning have shifted in the present era, and how that function might be repurposed for her own ends.

Orr’s exhibition closed on October 15th.

— J. Garcia

Read more:

Elizabeth Orr at Bodega [Exhibition Site]