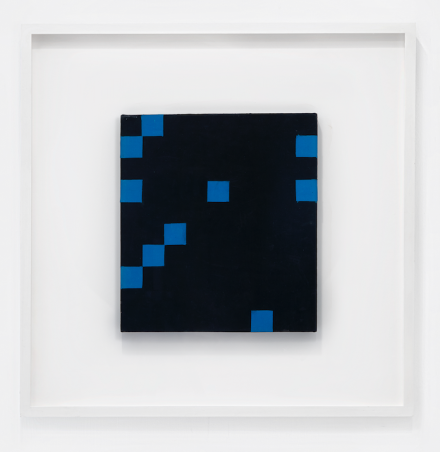

Heidi Bucher, Untitled (c. 1954) Photographed by Enrico FIorese.

With the Venice Biennale recently closing, only a few exhibitions remain on view in the city. Fortunately, for those who choose to visit this month, there is an exhibition at ALMA ZEVI featuring works by Heidi Bucher. Entitled Sublime Geometry, the show offers moments for discovery just as Venice harbors a wintry magic: in the quiet, crepuscular afternoon hours you arrive to this tucked away gallery space to find walls glowing with mother of pearl pigment.

Born in the Swiss town of Winterthur, Bucher studied textile design under Max Bill at the School of Applied Art in Zurich where she made silk collages that are enchanting for their varying degrees of precision and inexactitude. One work hangs in a corner of the gallery and invites closer inspection; illuminated from certain angles, it gives off a subtle luster redolent of a Vija Celmins Night Sky.

In 1975, Bucher acquired a former butcher’s freezing room as her Zurich studio, where she first created her iconic ‘skinnings’. To do so, she poured liquid latex and mother of pearl onto the tiled floors and walls and, after waiting for the cast to take hold, she peeled off the leathery film from the surfaces to create a physical reproduction of the space. In Bucher’s hands, latex beomes a messenger from the past, transmuting, informing, and crystallizing its future self. The ‘skinned’ impression is unyielding and frozen in time, yet the latex seems to decay before our eyes as the mother of pearl dries to resemble a weathered patina. Linking different temporalities like chrysalises, the artist drew this parallel with her oft-cited saying ‘Spaces are shells, are skins,’ and in this same regard would refer to a ‘skinning’ as the translucent shell of a larval state that signals the process of transformation. In this way, Bucher incorporated latex and mother of pearl as a ‘medium’ in the truest sense: a mutable substance that records the shell of a space in order to release it from spatiotemporal stasis.

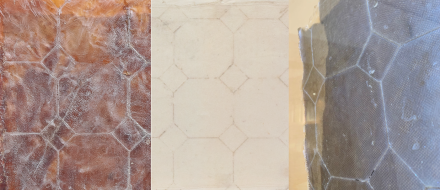

Heidi Bucher, Detail images of BORG (Kachelboden) (‘Tiled floor’) (1975-1977) (left to right) mother of pearl and latex on canvas; paper and glue; glue, latex, mother of pearl. Photographed by Quincy Childs.

Bucher referred to the first ‘skinnings’ of her Zurich studio as the Borg series, which translates to a ‘fortified castle’. This pun subverts, in a humorous way, the impression of those tiles, and the act of preserving them in an iridescent shimmer, to suggest the former opulence of a stately structure. Further wordplay in the show abounds: the plural form of latex is latices, a somewhat curious revelation considering that Bucher’s latex is originally a liquid substance, so to speak of many would infer a connected separateness. When dried, howver, this concept begins to take shape (quite literally) in the Borg skinnings. The exhibition features three such works that were ‘skinned’ in her Zurich studio between 1975-1977. These tableaux record the heptagonal-shaped tiles that, when presented together, form a lattice of latices. In the context of physics, the word ‘lattice’ denotes the accumulation of atoms at the molecular scale, and is known in this instance as a crystal. (A fitting nomenclature in light of the artist’s signature use of pearl pigment.) What is more, the gallery’s title sheet informs me that the word for ‘latex’ in Italian is in fact lattice, indicating yet another etymological opening in this trellis of translations.

Following the Borg series, Bucher shifted her emphasis to more autobiographical spaces. In a series entitled Herrenzimmer, she ‘skins’ her childhood home through a starkly new lens. She was particularly drawn to the parquet floor of her father’s study, presumably a room she would not have been let into as a child. The resulting works 8 and 45 der Parkettboden from 1979 therefore could be interpreted as a portrait of her father, suggests Zevi. She later ‘skins’ another family home called Ahnenhaus (‘Ancestral Home’) after hearing of its imminent demolition. She responds to this event by skinning the interiors to release them not only from their erstwhile states but also from their future disappearance, transforming the rooms into pellucid dreamscapes that would endure.

Heidi Bucher, 45 Der Parkettboden des Herrenzimmer in Wülflingen, Winterthur, (1979), latex, textile, and mother of pearl. Photographed by Enrico FIorese.

Heidi Bucher, Untitled (Plättlituch), ‘Flat cloth’ (1981), floorpiece probably from Ahnenhaus, Winterthur, mother of pearl, latex, textile. Photographed by Enrico FIorese.

One such work from Ahnenhaus is a floor-skinning called Plättlituch from 1981. This work presents the tension point, like the central cog of a wheel, around which her aesthetic concerns revolve. The square cloth is comprised of corrugated chevrons that form, like most of her skinnings, a Modernist grid. The material base of this work, however, resembles a napkin or dishcloth; clearly a textile, the material carries an unspoken stigma attached to it as ‘feminine’. (Notable women artists, such as Anni Albers for example, were initially redirected from painting studios to weaving workshops.) The ‘skinnings’ thus present two contrasting elements that drive her work—the superimposing of the serial onto the woven through the medium of latex. This dichotomy is indicative of a Post-Minimalist interest in using the material world as a template for sculpture. Owing to Bucher’s choice to cast architectural surfaces with geometric, serial patterns, e.g. tiled floors, geometric moulding, and napkins, she effectively uses the grid to break away from it. In this sense Bucher undermines, even satirizes, the very sobriety and assuredness of Minimalist predilections to liberate—and celebrate—the very imperfections and imprecisions that her contemporaries wished to contain.

What is more, Bucher subverts Minimalist tenets in her ‘skinnings’ by taking up household objects to playfully overturn the rigidity of the grid. Her skinnings can be analyzed with regard to the parallel rise of Post-Minimalist art and Second-Wave Feminism during the 1960s-80s, even if these interests were not in the foreground of the artist’s conceptual focus. Women artists engaged with Minimalism’s recent legacy as ‘a new archive of forms for different kinds of appropriation in the present,’ (Wagner, 2016), and Bucher emphasizes the tactility of production by combining various methods of mending, recording, and preserving surfaces. Through her intensive investigation into the phenomenological experience of spaces, Bucher seamlessly integrated the contemporaneous themes of her peers: the architecture of public and private spaces, as well as Post-Minimalist issues of femininity and the body.

She unravels these tropes in two untitled works from 1979 in which she embalms two quilt sections by layering latex, paint, and mother of pearl pigment. These works continue to challenge our perception as they appear monumental in form yet minuscule in size. Bucher’s decision to embalm only the facade of the quilt cushion allows for a pink blush of fabric to appear from behind the work’s more mineral facade. The two- and three-dimensional nature of the work is balanced as equal parts sculptural and painterly, a dualist nature that recalls the strategic tromp l’œils of Claes Oldenburg’s soft sculptures. Further, her distinctive decision to embalm something so domiciliary and intimate as a quilt pays lighthearted homage to the unremarkable in life, that which is familiar yet rarely displayed—much like the interiors of a house.

Heidi Bucher, Untitled (approx. 1979), quilt object, textile, mother of pearl. Photographed by Enrico FIorese.

Another work of mention is somewhat of an outlier. Entitled Spuren Gummirelief Rot, this cerulean and fuchsia work protrudes from the wall with excrescence. We know that it was made in the early 1980s, however only Bucher knew precisely where it was ‘skinned’. The mysterious origins of the work lend it an enduring and timeless mystique when viewed up-close, quite like how a seashell amplifies what sounds like the ocean through an ambient resonance in the cavity. Despite the simplicity of this phenomenon, we rather choose to believe in a more surreal conjuring, which is that the common saying that a shell echoes its origins. In a similar way, Bucher transforms the pattern of scalloped floor tiles to resemble fish scales or an opaline conk shell, giving the work the impression that it was washed-up from the Venetian lagoon into the gallery and hung to dry.

Like a cryptic message for a detective, the artist’s fingerprints upon this work allow us to trace her sequence of movements upon the tiles, as though they form a cartographic grid of digital topography. This work thus underscores the incredibly tactile process that Bucher undertook to make her ‘skinnings’. The visibility of her fingerprints remind us, once more, of the calcified layering that makes up a seashell. The pearly smudges of her touch evoke the shiny nacre of a seashell, which occurs when crystal aragonite platelets diffract light. She extends this analogy with each smoothing gesture upon the pearl pigment: pressing down layer after layer until the ‘skinning’ bears resemblance to the exoskeleton of an invertebrate. Rather than displacing nature into the art space, Bucher displaces art to disguise itself as nature.

Heidi Bucher, Spuren Gummirelief Rot (c. 1980), latex, cotton, mother of pearl. Photo from The Estate of Heidi Bucher.

Following this line of logic, Sublime Geometry rings with a prescient lucidity after the recent flooding in Venice, where water levels reached 1.87 meters (6 feet, 1 inch) above sea level in mid-November. As historic buildings are increasingly exposed to interloping saltwater, the very architecture that defines the city is at risk of depletion through a process of salt crystallization. This occurs when readily soluble salts from the lagoon seep into building facades where they form lattice-shapes, bloom, and expand; this crystallization creates pressure overtime that can destroy a building’s masonry structure. This poses a great threat to Venice’s many wall paintings and frescoes, not to mention its distinct vernacular of Gothic lancet arches combined with Byzantine and Ottoman influences. For an artist so fascinated by the ocean, historic buildings, and crystallization, the growing threat of saltwater to the architectural shell of Venice due to climate change would have been of particular interest to Bucher. Perhaps she had in mind this future plight when drafting plans for a ‘skinning’ to exhibit in Venice, much in the same vein as Lord Byron who wrote in 1818: O Venice! Venice! when thy marble walls / Are level with the waters, there shall be / A cry of nations o’er thy sunken halls, / A loud lament along the sweeping sea!

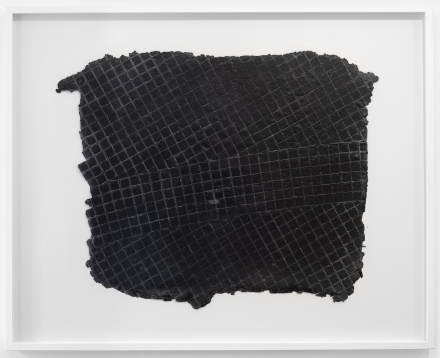

In a somewhat Rothkian vein, Bucher turns to black at the end of her life with her final floor ‘skinnings’. The spiky tesserae of the latex in Boden Dunkel, 1991, demonstrates an incredibly deft handiwork that is testimony to her decades-long investigation of the material. Zevi has insightfully placed this work adjacent to her early silk collage from 1954, creating a sense of circularity that ties together the show. These adjacent works, never before exhibited, share numerous affinities despite the chasm that marks their chronology: they both feature grids that deviate with an almost imperceptible caper leaving the matrixes askew. Although Bucher was certainly capable of aligning those squares (her numerous casts of tiles record perfect grid systems), what is rather at stake in these works is her ploy to deceive our perception. Through toying with materials, she prompts us to reconsider that which we take for granted in our perception of the phenomenal world.

Heidi Bucher, Boden Dunkel, (Dark Floor Piece), (1991), latex, textile. Photographed by Enrico FIorese.

The ‘skinnings’ on display present a prevailing paradox in form: they look at once durable and fragile, mutable and indissoluble; they are at first glance ethereal to behold, and yet when one looks closely, their surfaces appear to sphacelate before our eyes. The lighter works recall gauzy surgical dressings stretched to a gossamer translucence. The thicker skinnings, having grown tawny overtime, almost resemble a thin layer of flayed skin itself, invoking the explicit sobriquet of her practice. The show thus wrestles precisely with these dichotomies: the twofold process of simultaneously constructing and deconstructing space, casting moulds of a room only to cast away the ‘skins’. Central to Bucher’s concern was to create an indexical mark that was portable. Through her ‘skinnings’ she transformed rooms into dynamic, moveable entities to be freely exported, as something more plastic, something more free – like the memories they conjure. After all, as Bucher’s son Mayo shared with me, her work was all about freedom.

– Q. Childs

Cited Works:

Childs, Quincy. Haunting Häutungen: A Theoretical Inquiry into Heidi Bucher’s Kleines Glasportal (London: Courtauld Institute of Art, 2019).

McCarthy, C. ‘Toward a Definition of Interiority’, Space and Culture (vol. 8, no. 2, May 2005).

Wagner, Anne. ‘What Women Do, or the Poetics of Sculpture,’ in Revolution in the Making: Abstract Sculpture by Women 1947-2016, ed. E Rothrum (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016), 83.

Zevi, Alma. Heidi Bucher (Milan: Skira, 2019).

The Approach London. (2013) Heidi Bucher: ‘Rooms are Surroundings, are Skins’ [Online Press Release] 14 November. https://theapproach.co.uk/exhibitions/heidi-bucher-3/press- release/ (Accessed 12 March, 2019).

Alma Zevi. (2017) Heidi Bucher – Gordon Matta-Clark: Floors [Online Press Release]. Available at: http://www.almazevi.com/exhibitions/venice/134/heidi-bucher-and-gordon-matta- clark/ (Accessed: 20 March 2019).

Alma Zevi. (2019) Heidi Bucher: Sublime Geometry [Online Press Release]. Available at: http://www.almazevi.com/exhibitions/venice/293/sublime-geometry/ (Accessed: 15 October 2019).