The Central Pavilion of the Venice Biennale, via Art Observed

Spread between above the green lawns and trees of Venice’s Giardini, and the winding streets and canals of the Arsenale nearby, the Venice Biennale’s Central Pavilion has opened its doors for its Vernissage event, kicking off the 57th annual edition of the exhibition, and welcoming visitors to its first open viewings before it opens to the public this coming Saturday.

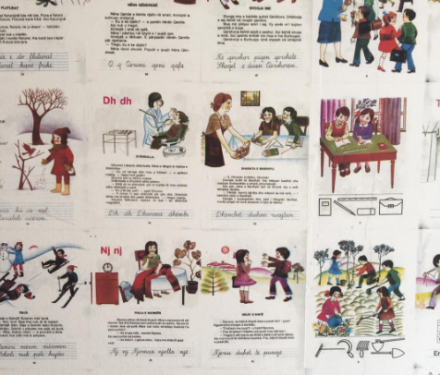

Wallpaper by Petrit Halilaj, via Art Observed

The show, curated by Christine Macel, has caused some murmurings during the early months of 2017, both for the increasingly fraught political landscape of global politics, and for a subtly a-political tone struck by Macel in her interviews leading up to the exhibition, a distinct contrast with the aggressive tone and engagement charted by previous curator Okwui Enwezor. Yet Macel was decidedly more vocal during the press preview event, taking on her critics with an opening address that underscored the prominence contemporary art might take (or perhaps already does) in the world around us. Specifically, she emphasized process, the act of creating and the internal monologues (or even dialogues) that ultimately bring the artist’s internal worlds and visions to bear on canvas, on video, on stage, or otherwise.

Olafur Eliasson’s Green Light Workshop, via Art Observed

The exhibition itself is a sprawling affair, with works spread throughout the Central Pavilion and Arsenale, and spilling out into the streets of the city around each venue. These sections are subdivided into a series of sub-pavilions, each of which contains its own selection of artists and these. With 9 separate sections, the show seeks to explore a broad expanse of processes and procedures artists take in bringing their work to life, and perhaps several potential solutions to fixing the problems of the world these works now reside in.

At the Giardini, the main exhibition splits itself between Artists and Books, and another section called Joys and Fears, each of which explores its unique perspective on the artist’s work both in the world around them, and in the internalized systems they create, nurture and manipulate in order to produce and sustain their work. Artists and Books places particular interest on libraries, systems of knowing and explorations of knowledge itself as modes of practice an interpretation. In one room, artist Hassan Sharif presents several rows of his works, mounted on commercial shelving, an intriguing turn on the concept of the archive that represents his work as both commercial material and archival representation.

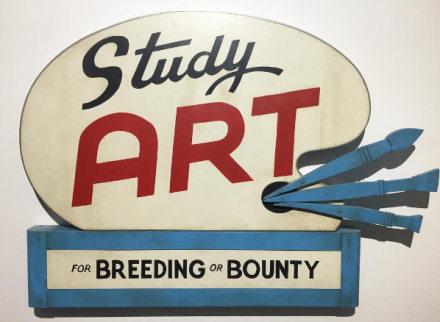

John Waters implores visitors to “Study Art,” via Art Observed

In another corner, artists Katherine Nuñez and Issay Rodriguez were presenting a small sculptural project bearing a strong similarity to a studio space, complete with stacked books and small fragments of work that echoed the concept of collecting and compiling as an act of artistic practice. The work gave off a sense of a world surging forth from the gradual accumulation of ideas, as if the continued act of practice eventually gave birth to its own self-sustaining universe. Also of note are a peculiar body of works upstairs by Raymond Hains, which mixes socially engaged photography with digital design and sculpture to create unique formal dialogues functioning on multiple levels and modes of understanding.

Philippe Parreno, Cloud Oktas (2017), via Art Observed

Elsewhere, artist Olafur Eliasson was presenting his “Green Light Workshop,” inviting visitors to work alongside a series of former refugees now living in Venice to create small geometric lighting structures, which were being 3D printed on-site, and which could be arranged in various configurations to create modular lighting structures. Drawing deeply on previous work mingling the artist’s own practice with lighting technologies with sustainable economic models and concepts of mutual benefit, the work took up a massive space in the center of the exhibition, with many visitors milling about or peering over the shoulders of others carefully assembling their light systems.

Katherine Nuñez and Issay Rodriguez, via Art Observed

A brief talk by the Mondrian Fan Club Outside the Pavilion, via Art Observed

Moving deeper into the Central Pavilion brought the viewer to the Pavilion of Joys and Fears, a more nuanced and often psychological selection of pieces, drawing on artist’s personal experiences and playful interpretations of the world around them. In one room, artist Senga Nengudi’s iconic utilizations of industrial materials and pantyhose create a suspended sense of the human form, mixing together iconographies of the body and technology to underscore a hybridized perception of humanity, and the psychological baggage that comes with it, while in a secluded room nearby, Andy Hope 1930 (alter ego of artist Andreas Hofer) combines homages to the golden age of surrealism with a series of twisted pop homages on canvas, bringing personal narrative and pop imagery to bear on the artist’s own experience of the world. Taking a similar approach with vastly different results are a subdued series of portraits by Kiki Smith, embellishing depictions of her sitters with slight details like flowers and other flora, or subtle repetitions in the bodies themselves.

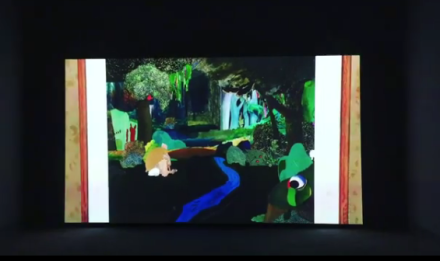

Work by Charles Atlas, via Art Observed

By contrast, artist Rachel Rose’s video work in this section is an undulating visual puzzle, washing glitchy visuals and colorful asides over daily routines, building abstracted narratives that fill the viewer with both the joy and anxiety that Macel’s grouping promises.

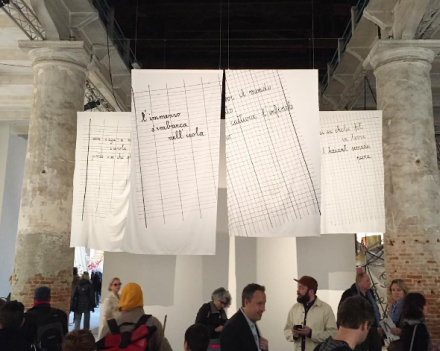

Maria Lai at the Arsenale, via Art Observed

At the Arsenale, another series of seven pavilions run in a straight progression through the connected halls and chambers of the massive 12th century structure, continuing the show’s series of progressing themes marking engagement with the present era, the artist’s craft, and the futures it may one day make possible, with works leading the way through the show in a manner that encourages intersection, conversation and investigation of nuanced links and exchanges of perspective from one space to the next.

Franz Erhard Walther, Wall Formation ‘Yellow Modeling’ (1985), via Art Observed

The show begins with the Pavilion of the Common, a program drawing on shared experiences of space and the possibilities of art to build consensus through varied modes of seeing, thinking or understanding. Shared identities and perspectives are a common theme here, as are visual mazes and interrogations of historical forms. Particularly striking are the works of Franz Erhard Walther, whose playful embrace of minimalism, and the replication of its formal characteristics through the often crooked, floppy materiality of fiber arts blurs lines between each form, imbuing a high modernist thematic with distinct undertones of the traditionally feminine fields of craft.

Martin Cordiano, Common Places (2017), via Art Observed

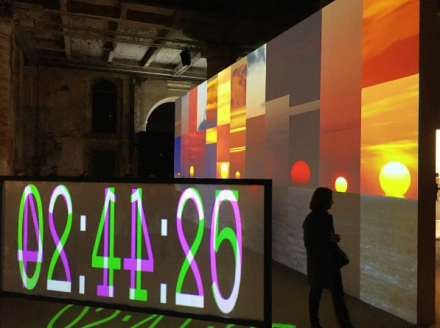

In the next section, Pavilion of the Earth, the show took one of its harder turns towards the political, perhaps an unavoidable situation in an era of the rampant problems caused by climate change, and the still fraught language used to discuss its impact, not to mention the political implications of global community in parallel with any natural or ecological situation. The section opened with a powerful new Charles Atlas work, The Tyranny of Consciousness, which reprised his collaboration with New York drag icon Lady Bunny to explore the potentials for political agency in the modern era, backdropped against one of his video collages depicting various setting suns. In another corner, artist Thu Van Tran was presenting a body of work exploring her relationship to the rubber plants in her home country of Vietnam, and the oppositions of her own identity with the market for both this rubber and her own art works by the globalized neoliberal market place.

Charles Atlas, The Tyranny of Consciousness (2017), via Art Observed

Michel Blazy, Collection of Shoes (2016-2017), via Art Observed

At the Pavilion of Traditions, a more human-centric thread took the day, with pieces delving into historically and culturally resonant objects and materials positioned in new forms, yet drawing heavily on their presentation as a response to their past, present and future contexts. In one corner, Irina Korina’s Good Intentions pulled viewers into a small steel staircase, allowing them to pass into a separate room filled with neon lights and floral arrangements, each object drawing on its unique materiality and presence in such a close-cropped space to create an explosive encounter for intrepid visitors.

Irina Korina, Good Intentions (2017), via Art Observed

In the next section, Pavilion of Shamans, takes a similar reliance on the human spirit, and twists it towards the surreal and otherworldly, with projects and installations delving into humanity’s desire for spiritual connection and awakening. Ernesto Neto is showing a iteration of his finger-crocheted hut works, creating a communal zone for visitors to sit and rest inside the fair, as chairs, couches, and the odd musical instrument offer a relaxing zone to decompress and meet fellow exhibition-goers. By contrast, artist Rina Banerjee was mining a distinctly tense energy, with natural material, glass-work and string that created a twisted, offset sense of balance on the walls of the exhibition.

Work by Achraf Touloub, via Art Observed

Ernesto Neto, A Sacred Place (2017), via Art Observed

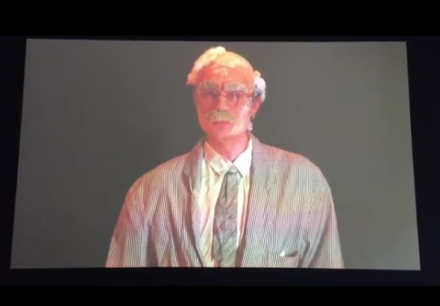

In the next section, the Dionysian Pavilion, the Greek god serves as a fitting focal point for a section celebrating the feminine, in conjunction with a sense of sexuality and self-expression that sees distinct interpretations of music and the artistic impulse, perhaps best seen in Kader Attia’s installation just off the main path of the show. Cataloguing a range of music by Algerian musicians like Warda Al-Jazairia and texts exploring the power and musicality of the human voice, Attia builds the viewer to a shared sense of harmonic and aesthetic interrelation with a range of cultures, before bringing this shared sense crashing under a series of brutal poems cataloguing the rape and abuse of power perpetuated against the people of the Middle East by unspoken globale powers. Placing such plaintive words in the voices of untrained actors, the power of its words only seems amplified ever louder. Elsewhere in the space, works like a series of clothing pieces by Huguette Caland turn the female body towards a more universal symbol of ritual and celebration, adorning figures with robes crafted to play on the sexual organs and identities of their female wearers.

Karla Black, Presumption Prevails (2017), via Art Observed

Moving towards the end of the exhibition, Macel’s selection breaks with her exploration of the expressive range of human tradition and history, using her previous section’s prompts of the more heightened states of human creativity to delve into works expressing intense creative energies in her Pavilion of Colors. These pieces, filled with powerful energy and decisive approaches to the work’s execution, presents a section that amplifies the act of human connection to its most primal, formal elements. In one corner, a Karla Black piece streams down from the ceiling, filling the space with luscious, creamy colors and gentle rips and twists of paper that belie the simple materials the work is composed of. Only a few feet away, Sheila Hicks’s Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands moves in a similar direction, using fiber materials to flood the corner of the room with massive blooms of sumptuous reds, blues and greens.

Sheila Hicks, Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands (2016-2017), via Art Observed

The exhibition brings itself to a close with the a final series of works looking out into an unspecified space and time. The Pavilion of Time and Infinity begins in the last room of the Arsenale and concludes out in the Giardino Delle Vergini, where a selection of video works trace a quasi-spiritual engagement with the artist’s practice (like in Salvatore Arancio’s video work, or a special project by Michael Beutler, featuring a massive wooden pavilion placed up on a series of floating blocks, leaving the entire work floating back and forth in the wind. But it’s Alicja Kwade’s beautiful WeltenLinie that truly closes out the exhibition, a surreal hall of mirrors that sees viewers passing in and out of reflecting panes of glass and through metal frames that give the entire space a feeling out of time, gradually erasing other visitors from one’ s line of sight or leaving one suddenly alone in a corner.

Alicja Kwade, WeltenLinie (2017), via Art Observed

Macel’s exhibition excels at moments like this, when the artist’s work reaches the apex of its transformative capabilities or aesthetic process, and unfolds into moments of poignant understanding, or surreal, meditative quiet. Perhaps its a sense of patience that the curator is truly arguing for, an art (and viewer) willing to give itself over fully to the progression and development of a piece, and the modes of understanding the gradually emerge from them. If that understanding and willingness to empathize becomes the lasting impression of this exhibition, perhaps Macel’s work on the Biennale does offer a way forward for the world outside the gallery after all.

A work by Rina Banerjee, via Art Observed

Raymond Hains, via Art Observed

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Venice Biennale: Viva Arte Viva [Exhibition Site]

A Venice Biennale About Art, With the Politics Muted [NYT]

A Look at ‘Viva Arte Viva,’ the Hippie, Heal-the-World Venice Biennale [Art News]

‘Reinventing the world’: Venice Biennale gives older and lesser-known artists their due [Art Newspaper]