Raul de Nieves, via Art Observed

It’s been a long time coming for this year’s Whitney Biennial, an exhibition that has sat on pause for several years as the institution prepared for its move downtown, and got comfortable in its new space in the Meatpacking District. Opening its first Biennial since 2014, the stage has been set for a particularly timely moment of reflection on both America and its art communities at a time when the national identity has rarely been so fiercely contested and examined.

Ajay Kurian, Childermass (2017), via Art Observed

Co-curated by Christopher Y. Lew and Mia Locks, the exhibition draws on the pair’s extensive vocabulary and nuanced perspective on modern art production around the globe, pulling from a range of artists that never feels particularly top-heavy or overly ponderous. Critiques of the modern museum organizational structure by Occupy Museums co-exist with playful, socially-engaged video pieces by Maya Stovall (whose Liquor Store Theatre sees her choreographing performances outside liquor stores on Detroit’s East Side), while elsewhere, subdued domestic scenes by Celeste Dupuy-Spencer give way to Raul de Nieves show-stopping stained glass work and beaded sculptures, contrasts in the perception and understanding of modernity that manages to glorify and examine simultaneously.

Pope.L, Claim (2017), via Art Observed

Considering the flexibility of the museum’s exhibition spaces in its new building, the Biennial manages to feel both endlessly expansive and equally manageable, welcoming exploration that winds the viewer into small alcoves and corridors where digital pieces and video work offer momentary changes in pace and scale from the main galleries. In one corner, a lyrical Anicka Yi video work draws on intersections of 3-D video and research to create a haunting flow of images, while nearby, Samara Golden’s spectacular mirrored installation creates the illusion of an abandoned retail complex, dystopian in its slurs of material and sleeping figures installed well below the viewer’s vantage point. This sense of space is expanded upon by Jessi Reaves, whose utility-driven furniture sculptures are spread throughout the exhibition (and even in some of the museum’s conference rooms and meeting spaces), highlighting and repositioning the space itself as both aesthetically-oriented yet driven by certain functional demands.

Asad Raza, Mother Tongue (2017), via Art Observed

The digital as spectacle also makes its presence distinctly felt, perhaps most notably on the fifth floor, where a series of automated Jon Kessler works continue the artist’s comical engagement with the body and technology through absurdist assemblages, and one floor up with Jordan Wolfson’s 3-D work Real violence, which will surely go down as one of the show’s most controversial works. Depicting the artist savagely assaulting a digital avatar, both with a bat and with repeated kicks, the work sees countless viewers leaving the space with an uneasy look on their faces, having had a first-hand glimpse of real violence rarely seen in a museum space.

This is the sense of modernity that the Biennial manages to capture so adroitly, a world teetering on the edge of full-scale violence and collapse, negotiating tensions all the while through social mediation and grandiose expressions of humanity. It’s perhaps most telling that a work like Wolfson’s could be complemented so strongly by that of artist Asad Raza’s nearby. The piece, featuring a series of repotted plants spread throughout one of the gallery rooms, is joined by a series of caretakers/performers, who talk to viewers about the plants, their own lives, and the objects spread throughout the room, increasing the work’s mystery and allure as the viewer’s relationship to the space evolves.

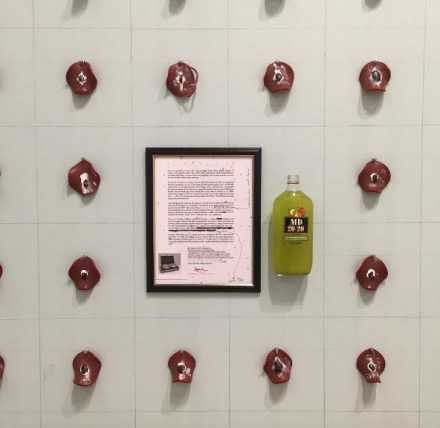

Works by KAYA, via Art Observed

John Riepenhoff featuring video by Saige Rowe, via Art Observed

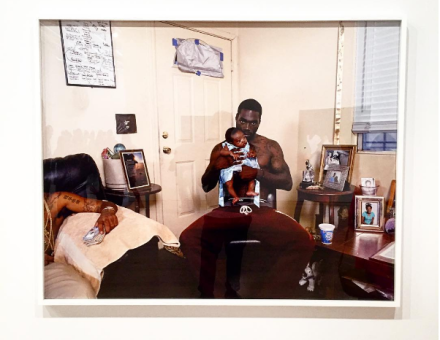

These threads of social engagement, identity and narrative converge throughout the exhibition in a number of forms, from Henry Taylor and Deana Lawson’s powerful renderings of Black America to Pope.L’s ominous Claim, featuring sweating, stained slices of baloney covered with human faces, a comment on mass-scale data collection and the inherent potential for discrimination and oppression that it welcomes. These find a striking counterpoint in the work of Puppies Puppies on view, Triggers, which show the triggers pulled from deactivated handguns, distilling the violence inherent in their use down to the moment at which violence intent moves from the human to the machine.

John Riepenhoff featuring video work by Saige Rowe, via Art Observed

Perhaps this is the strongest point to consider in relation to the show at large. Despite the most ominous notes sounded by the exhibition in terms of violence and oppression, human error or technological accumulation, the show manages to keep the agency of human behavior in view, a point that sounds loudest in both the show’s darkest and most jubilant moments.

The exhibition closes June 11th.

Henry Taylor, The 4th (2012 – 2017), via Art Observed

A work by Jessi Reaves, via Art Observed

Deana Lawson, via Art Observed

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Whitney Bienial [Exhibition Site]

A User’s Guide to the Whitney Biennial [NYT]

An Early Look at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, Arriving in Time to Tackle America’s Turmoil [W]

The 2017 Whitney Biennial Is a Moving, Forward-Looking Tour de Force—a Triumph [Art News]