Phyllida Barlow, Folly at the British Pavilion, via Art Observed

Spread out across the Giardini and the various storehouses and spaces inside the Arsenale, the Venice Biennale‘s annual invitations to various nations around the globe serves to offer a counterpoint to the sprawling main exhibition, Viva Arte Viva. Presented by individual curators and supported by art institutions back home, the shows offer not only a selection of singular voices from around the globe, but equally a look at the various national discourses of each country’s artistic institutions and infrastructure, a point that equally sets it as a strong conversation piece against the curatorial discipline of the main exhibition’s lone organizer, in this case Centre Pompidou’s Christine Macel.

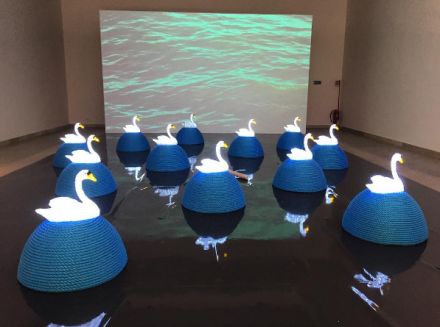

Jana Zelibska at the Czech Republic Pavilion, via Art Observed

The Biennale’s national exhibitions center around the Giardini’s main pavilions, where the long-held exhibition spaces bearing the names of their countries are spread across winding paths and green hills. The environment gives a well-separated browsing experience, where each artist is provided carte blanche to realize their vision inside the space, often responding to architectural elements or working in direct opposition to the spaces themselves. Yet the predominant theme throughout the Giardini seemed to be an embrace of chaos, with many works delving into hybrid situations or inversions of space that forced the viewer to negotiate with the iconographies and structures they found themselves placed within.

Phyllida Barlow, Folly at the British Pavilion, via Art Observed

Phyllida Barlow, Folly at the British Pavilion, via Art Observed

In that framework, few could compare with artist Phylllida Barlow, whose towering, playful sculptures and lumpy masses of material that often disrupted the walking paths of visitors, making the galleries often too close for comfort, yet nevertheless quite entertaining. Barlow’s work here is an impressive step for the artist, one that sees her reaching her peak on the most prominent of stages. Just outside, artist Geoffrey Farmer had reduced the Canadian Pavilion to a pile of wood and a central fountain, which would occasionally burst through the holes in the ceiling of the pavilion. It was an intriguing note, one that saw the artist turning the pavilion inside out, and leaving its central column exposed to the world around it amidst the chaos of its deconstruction.

Xavier Veilhan, Merzbau Music (Installation View), via Art Observed

Similar chaos was going on just across the way at the French Pavilion, where Xavier Veilhan’s Music Merzbau had opened its doors. Curated by Lionel Bovier and Christian Marclay, the exhibition took the form of a strikingly-designed music studio, filled with jutting corners and complex patterned panelling, within which a group of performers were tearing into a pair of massively-scaled string instruments. Veilhan’s project will host jam sessions and musical collaborations all summer, recording and archiving the music while visitors pass through the space.

Xavier Veilhan, Merzbau Music (Installation View), via Art Observed

Anne Imhof, Faust at the German Pavilion, via Art Observed

But for musical and performative chaos, few could top artist Anne Imhof, whose operatic performance work Faust has already become the talk of the Biennale. Incorporating a range of youthful performers whose languid poses and unexpected gestures moved from the main exhibition floor to underneath (where performers could be seen lighting fluids on fire or laying across the ground and staring up at the viewer), the show was a direct challenge to spectatorship and its effects on the body, confronting the realm of emotions and aesthetics as exchangeable commodities, and the ability of the body in movement to disrupt these forces. Even as visitors snapped photos or stared up at a performer suddenly bursting into song, one could not avoid the constant alterations of roles between performer and viewer, all soundtracked by a sludgy, droning score, and punctuated by the barking of caged dogs just outside.

Anne Imhof, Faust at the German Pavilion, via Art Observed

Anne Imhof, Faust at the German Pavilion, via Art Observed

Mark Bradford, Spoiled Foot (2016), via Art Observed

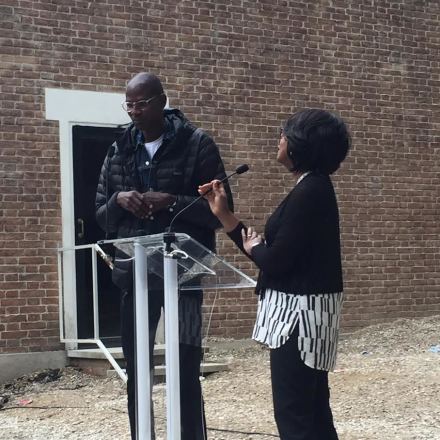

Following such a jarring performance, a trip to Mark Bradford’s exhibition at the American pavilion might be in order, where the artist’s subdued but powerful body of works addresses similar themes of loss, time and the body in an engagement with modernity, yet offers a distinctly more soulful, material bent, twisting his canvases into vivid expressions of energy that offer a note of continuity and stability in a trying political moment for the United States. “An artist doesn’t have any more responsibility than a doctor does to change the world,” Bradford said during the opening press conference. “I see possibility based on conversations we’re having it. Its always about navigation and negotiation, not roadblocks. We can’t disappear because we’re nervous and scared.”

Mark Bradford at the American Pavilion, via Art Observed

Mark Bradford, Saturn Returns (2013-2017), via Art Observed

Brigitte Kowanz at the Austrian Pavilion, via Art Observed

At the Austrian Pavilion, Erwin Wurm presents work with Brigitte Kowanz, combining the snarky One Minute Sculpture series with Kowanz’s dazzling light displays, mounted on mirrors to create an illusory spatial environment that balanced well with the stone-faced performers climbing onto and off of Wurm’s works outside. A similar brand of spatial inversion was presented at the Japanese pavilion, where Takahiro Iwasaki sculptural works served as a backdrop for a strange installation in the floor of the space, allowing visitors to pop their heads up through a hole to situate themselves in a miniature environment, and stare up at the viewers just above them. It was a bizarre arrangement of space, which caused the hanging works around the hole to take on multiple dimensions and perspectives simultaneously, and to encourage varied perspectives on the true orientation of the exhibition.

Erwin Wurm at the Austrian Pavilion, via Art Observed

Erwin Wurm at the Austrian Pavilion, via Art Observed

The Brazilian Pavilion offered a more considered experience of space, with artist Cinthia Marcelle installing a series of works amid a grated, slanted floor filled with stones. The strange perceptual effects, with bumps and crooked walking paths balanced by stark, minimalist sculptures. Long tubes of hose contended with strips of paper on the wall, or a lone TV playing a loop of tiles being removed from a roof, creating a gradual, meditative space that is a welcome change from the sensory overload of many other pavilions nearby.

Canadian Pavilion by Geoffrey Farmer, via Art Observed

At the Arsenale, a smaller set of National Pavilions offered a close counterpoint to the thematic exhibition Viva Arte Viva on view in the first half of the exhibition space. Moving out from the conclusion of the show, the fair turned quickly towards the national concerns of countries like Mexico, where artist Carlos Amorales was presenting a body of works which explore hybridized forms inspired by the writings of Henri Michaux. Foregoing easy legibility as sculpted objects or standalone prints, the works’ shared forms created a series of variations and alterations that challenged the viewer to connect each work on a more primal, perceptual level.

Carol Bove at the Swiss Pavilion, via Art Observed

Carol Bove with her Installations at the Swiss Pavilion, via Art Observed

Bernardo Oyarzun at the Chile Pavilion, via Art Observed

By contrast, the Philippine Pavilion turned its focus towards more literal readings of the political, exploring the work of Manuel Ocampo and Lani Maestro, both national ex-pats whose work reflects the respective eras and political milieus that ultimately caused them to flee their home countries. In the next room, Chile’s pavilion space included a single monumental installation by Bernardo Oyarzun, a massive circular accumulation of primitive masks surrounded by scrolling wall texts that offered an ominous negotiation between ancient histories and modernity. A divergent approach to the concept of national identity came from Tunisia, whose pavilion offered a series of passports turning its holders into citizens of a space outside easy readings of national affiliation, artificial documents referred to as “Freesas” (although holders were encouraged not to present them at national borders).

Carlos Amorales at the Mexican Pavilion, via Art Observed

The Tunisian Pavilion offers readymade passports to visitors, via Art Observed

The Malta Pavilions anti-hierarchical display of art and artifacts marks its third time in Venice, via Art Observed

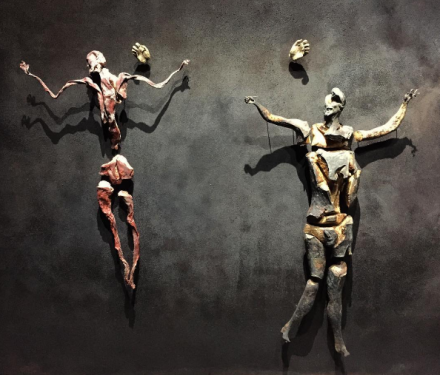

Yet few installations at the Arsenale could compare with the masterful work on view at the Italian pavilion, where High Line Art curator Cecelia Alemani had culled together a haunting selection of works by Roberto Cuoghi, Adelita Husni-Bey and Giorgio Andreotta Calò, which mixed together various shades of concrete identities, dark atmospherics and experimental processes that made it an unforgettable progression through space. Entering the exhibition space, one is immediately confronted by Cuoghi’s sprawling factory space, titled Imitazione di Cristo. Creating multiple copies of the crucified Christ through hybrid casting procedures, Cuoghi’s installation traces these bodies as they decay and age, moving them through a sterile plastic bubble before breaking them down into raw materials on the other end and beginning the process again. The cyclical process and the often jarring combination of decayed bodies and the smells of their organic materials, in conversation with the industrial material surrounding the space, ultimately presented a distinctly challenging exploration of the Italian Catholic iconography, and the modern technologies underscoring the processes of illness and bodily decay paralleled with the constructs of the eternal in the Christ mythology. This gave itself over to Husni-Bey’s work, depicting a group of New York City children discussing the future of humanity, and the constructs of capitalism that ultimately overshadow the destructive processes that underwrite modern civilization. Offering a hopeful look at a generation painfully aware of their place and role in the conservation and preservation of the planet, the artist seems to offer a faint glimmer of hope against Cuoghi’s cyclical processes of collapse and reconstruction.

Roberto Cuoghi at the Italian Pavilion, via Art Observed

Roberto Cuoghi at the Italian Pavilion, via Art Observed

Adelita Husni-Bey at the Italian Pavilion, via Art Observed

In the middle of these two systems lives Calò’s immense mirage, a shadowy expanse of space laid out over the top of a massive scaffolding structure giving off the impression of a near boundless expansion of space. Spreading water over the scaffolding viewers walk beneath and ultimately climb to view the fantastic image, the artist’s work seems to underscore the heights, and depths, of human possibility. Even as Calò’s work underscores the figures creeping beneath such a fantastic vision, his work offers a moment of ecstatic wonder, an ephemeral illusion built on concrete structures. As the viewer walks out from the space shortly after viewing his piece, this trio of vantage points seems to offer both hope and challenges to the future of humanity, each underscored by a sense of an ever-expanding vocabulary of the possible.

Giorgio Andreotta Calo at the Italian Pavilion, via Art Observed

Lani Maestro at the Philippine Pavilion, via Art Observed

Beyond these two locations, a number of other exhibition spaces around Venice were hosting pavilions and installation projects. Just a few minutes away from the Palazzo Grassi, the Estonian pavilion presents Katja Novitskova‘s enigmatic sculptural displays. Combining cut-out images of the natural world in conjunction with neon lights and strange assemblages of modern tech, the artist’s work conjured a future negotiating between the language of a pure nature and the increasing intrusion of modern tech into the realm of the biological. Animals glow with a gentle yellow backlight, while floating texts bring up concepts of artificial fertilization and digital imaging of behavioral patterns, delving into a world where the increasing wealth of data renders the broader globe increasingly visible, and ever closer to our realm of control and co-evolution.

Roberto Cuoghi at the Italian Pavilion, via Art Observed

NSK State Pavilion, via Art Observed

Also of note was the NSK Pavilion, located just south of the Grand Canal in the Cannaregio district of the city. An ongoing project of a group of European philosophers and artists, the exhibition here challenged easy readings of the concept of the state, often actively disrupting the act of legibility or access. A portion of the exhibition was tilted on a fierce angle, making visitors climb up a steep slope to access works on one end of the space, while passage through to the other side saw a shifting landscape of desks and paperwork, where moving ladders and walkways made it difficult to interact with each piece of the show, and leaving the viewer’s relationship to its prompts relatively uncertain. In an era of increasing economic precariousness and fiercely maintained borders, the show’s physical prompts were a refreshing engagement with the political, not only acting as a space for distributing knowledge, but equally for embodying the struggles of this era within the viewer themselves.

Olaf Nicolai serves hot chocolate at A Plus A Gallery this morning, via Art Observed

On a lighter note, for the next few weeks visitors can pay an early visit to A Plus A Gallery this summer, where the “Breakfast Pavilion” offers a range of sweets, fruit and espresso to art lovers getting ready to start their day, capped off by cooking sessions and special installations by a range of artists. Olaf Nicolai was behind the stove when Art Observed dropped by this morning, serving up his own recipe for homemade hot chocolate, boiled down from a chocolate sculpture depicting the head of Marcel Duchamp in the aeroceramica style of futurist Renato Bertelli, a coy, and delicious, nod to the history of the Italian avant-garde.

The Breakfast Pavilion at A Plus A, via Art Observed

Of course, the sheer scale of the Biennale makes a full summary almost impossible, and the distributed nature of much of the event’s programming is half the fun of the event. There are countless more installations and projects spread throughout Venice, within reach of any intrepid visitor.

The exhibition closes November 26.

Erwin Wurm’s One Minute Sculptures at the Austrian Pavilion, via Art Observed

Xavier Veilhan, Merzbau Music (Installation View), via Art Observed

Carol Bove at the Swiss Pavilion, via Art Observed

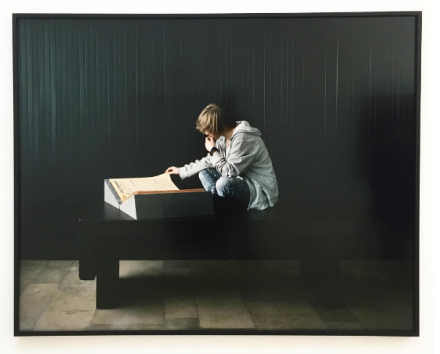

Sharon Lockhart at the Polish Pavilion, via Art Observed

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Venice Biennale [Exhibition Site]

57th Venice Biennale: Arsenale Pavilions [Frieze]