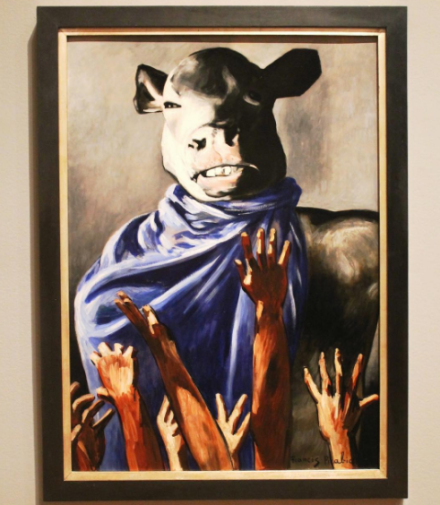

Francis Picabia, The Adoration of the Calf (1941-42), via Art Observed

Taking on the endlessly inventive and ever-shifting formal abilities of artist Francis Picabia, MoMA’s current survey dedicated to the painter (and the first of its kind in the United States) has earned almost ceaseless praise, diving deep into the fluid and challenging series paintings, poems, published works, performances and films of one of French surrealisms landmark voices. Spread across the gallery’s sixth floor exhibition space, Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction (which closes at the end of the week), serves as both a striking introduction and an impressively deep elaboration on the artist’s body of work.

‘

‘

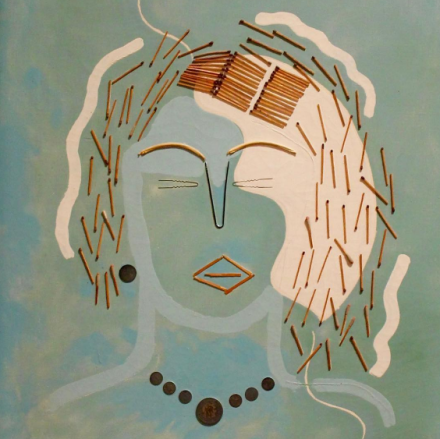

Francis Picabia, Match Woman (1924-25), via Art Observed

Born in Paris near the end of the 19th Century, Picabia’s arrival at artistic maturity was paralleled by the sweeping changes running through the European avant-garde, many of which find their way into his work during early career. Impressionist explorations give way to complex Cubist exercises in the artist’s early work, exchanging influence and interest with the concepts and formal irruptions of dada also running through the 20th Century’s early decades.

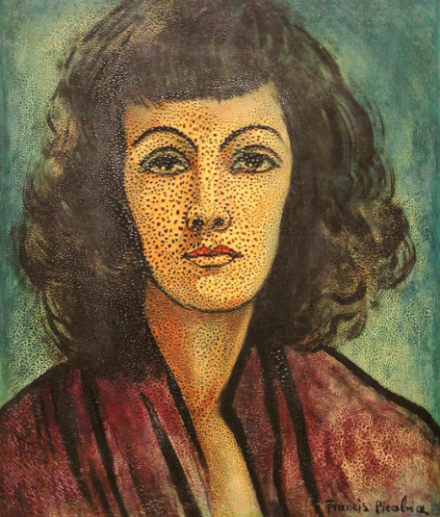

Francis Picabia, Portrait of a Woman (1935), via Art Observed

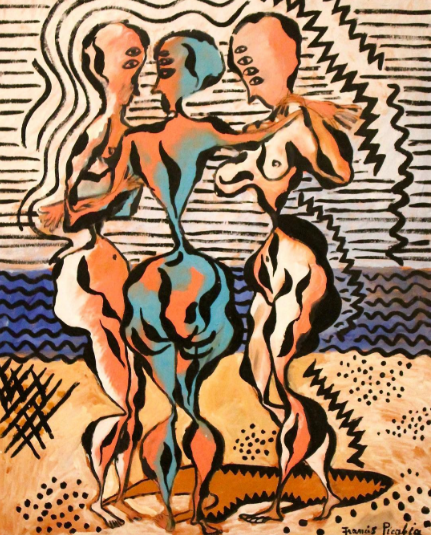

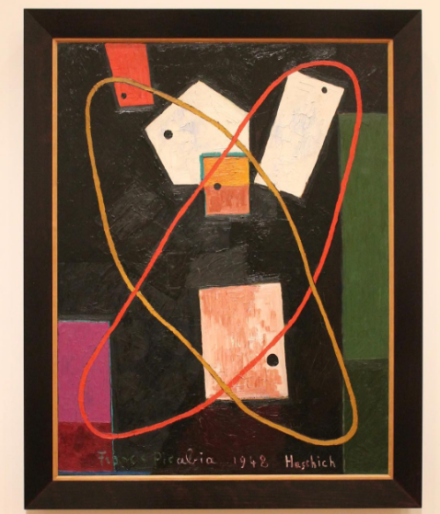

Yet the artist’s near-constant negotiation with the rapid changes of painterly style finds its way in and out of his work for many of the following decades of his work. Picabia’s masterful understanding of his materials, in conjunction with the histories they were engaged in allowed him an ability to change direction at a moment’s notice, moving from pointillist interrogations of the portrait to studious, light-washed explorations of surrealist imagery, particularly in works like his iconic The Adoration of the Calf, a masterfully rendered piece that twists some sense of the human form from the calf in a manner that distorts and subverts easy reading of the image. Elsewhere, his embrace of Dada in conjunction with his even-handed, painterly style leads to works like Match Woman, using ready-made materials as a sudden break with the artist’s studied, minimalist approach to figuration.

Francis Picabia, Comic Wedlock (1914), via Art Observed

If anything, it’s this ability that underscores Picabia’s mastery of his craft, and perhaps may have also left him as something of a riddle in the annals of painterly history. Rather than easy engagements with the image and its constructs that defined the artist’s contemporaries, Picabia is invested as much in breaking down the assumptions of genre and form as much as he is in disrupting the logic of the realist image. Picabia mixes forms as well as he does genres, always leaving a sense of the image as split between its initial visual contexts and the histories that bound them. It should be no wonder, then, that he would count Marcel Duchamp among his closest friends, another artist who has long eluded easy classification as much for his enigmatic works as for his push back against simple readings of pieces as just that. For both Duchamp and Picabia, the work is an extensions of broader networks; of modes of knowing, modes of seeing, and the human figures that bring these modes to life. Here at MoMA, these forms live again, echoing their historical resonance and masterful craft across the gallery walls.

The show is on view through March 19th.

Francis Picabia, The Three Gracias (1924-27), via Art Observed

Francis Picabia, Kalinga (1946), via Art Observed

Francis Picabia, Haschich (1948), via Art Observed

— D. Creahan

Read more:

Francis Picabia: Our Heads Are Round so Our Thoughts Can Change Direction [MoMa]